In a story that is abstract, hard to grasp and comprised of details and names science fiction writers might be jealous of, Kasperspy is finally able to point an indirect but definite finger at the NSA.

Last Monday, February 16th, at Kasperspy’s Security Analyst Summit, Kaspersky security researchers were finally prepared to present their findings linking the 15 year old NSA handle, “Equation Group”, to hundreds of files including plug-ins and upgraded variations going back fifteen years. Kasperspy operatives were initially able to identify the nls_933w.dll module by correlating a list of hard drive vendors in part of the code with a list of hardware commonly infected by a piece of code identified five years ago, dubbed the nls_933w.dll module.

Vitaly Kamluk is the voicebox for Kaspersky Lab’s Global Research and Analysis Team. He gave the now week-old-but-already-infamous talk, offering several long-coming answers to questions anyone interested in high-level cyber security have been otherwise fruitlessly asking for years. Kamluk explained that the module is in many ways the “ultimate cyberattack tool”. It’s possibly the crowning achievement of the so-called Equation Group. He explained how the available evidence implies Equation group is about 15-years-old and gave detailed reasons why the malware is evidence that the same group responsible for the nls_933w.dll module must have had confident and confidential knowledge of Stuxnet and Flame.Personally, I have trouble vetting the information to verify Kasperspy’s accusation, and it is difficult to link Equation Group to the NSA. This is the nature of information warfare, though; the people who are great at concealing intentions and information are going to be shrouded in mystery even after someone is able to accuse them. What makes Kasperspy vs. Equation Group so noteworthy is that a private security firm seems to have the clearest understanding of cyberwarfare, out of everyone who has the guts to openly discuss such a formidable potential enemy. Equation Group is known to be behind several security operations of dubious benefit to anyone other than the United States, with targets including the most-feared zero-day exploits that can literally ruin computers, including systems that are running critical military or utility functions for states. Equation Group has been accused without concrete proof of espionage against increasingly sensitive targets. The current list of victims includes governments, energy companies, embassies, telecoms and many other entities, mostly based in Russia, Syria, Iran and Pakistan.

The targets imply Equation Group is acting on behalf of US interests but until people know the endgame of such security violations or the true identity of Equation, there are more questions than answers – probably by design.

Read more about the internet:

World Cyberwar: Six Internet News Stories in 2015 Blur the Line Between Sci Fi and Reality

|

Jonathan Howard

Jonathan is a freelance writer living in Brooklyn, NY |

Leaks, Revenge Porn, Consent and the Future of Privacy in the Information Age

The tide is turning on revenge pornographers, “purveyors of sexually explicit media that is publicly shared online without the consent of the pictured individual”. In almost any public context on the internet, most Americans are almost unanimous in condemning the nature of the privacy violations behind revenge porn. Liberals who want the concept of consent front and center in any contemporary debate about sex have also lead the conversation about privacy debates and can easily get on board with the support for the overwhelmingly female victims of revenge porn. Conservatives could seize not only a new opportunity to regulate porn in a way that reaches across the aisle but chance to condemn an aspect of pornography. “Revenge porn mogul” might be the least likeable role the internet age has to offer and now it is poised to become one that marks the transition to the second generation raised on the internet. It’s a crime for the ages. Like a lot of what happens online, it’s being punished, legislated, debated, rising and hopefully falling – all within a generation.

Hunter Moore recently plead guilty to hacking charges and ultimately will be punished for a felony conspiracy to hack email accounts to access nude or pornographic pictures. Is there anyone supporting these revenge porn sites without acknowledging it as a vice? Any open supporters? How did revenge porn, something so universally frowned on, become a profitable business for multiple sites and their administrators? First of all, there is an audience for it. Pornography in general is a successful and diverse media industry but that industry is home to several active arguments. These arguments have fluctuating dynamics as the cultural contexts and tastes morph over time. When nudes are leaked or revenge porn is uploaded crucial aspects of other porn-related debates are accented. Aspects like: how consent is portrayed, how publishing rights are managed and protected, and how regular pornography use affects the human psyche. The number of porn watchers is so high the revenge sites were able to stay in business despite public outcry and condemnation.

Is revenge pornography going to persist despite the first steps toward a coming prohibition? Is there a coming prohibition? Will prohibition work?

What is the nature of the post-modern privacy debate? How much privacy can we guarantee ourselves under the current system, and how can we protect it? How is our right to privacy defined the evolving light of interactive media, smart devices, ubiquitous cameras and social media? How can one most effectively respond to privacy violations in the contemporary context?

A changing political landscape ahead for the privacy debate. Will the call for information transparency eventually prove to be a strong counter argument against individual privacy? If corporations, government workers, military entities and criminals outside the reach of current law enforcement are to be held accountable their privacy must be violated. The vocabulary changes and people begin to talk about security and the individual is actually tasked with protecting not only his or her own personal secrets but to sacrifice informational privacy for the sake of the group or entity’s security. People can feel threatened and become intimidated into complacency or even become complicit in information-related crimes. The material is vast and the precedent has yet to be set leaving employees subject to situations where the law has yet to be written, and a social doctrine isn’t yet forged.

Read more about the current state of the internet at:

World Cyberwar: Six Internet News Stories in 2015 Blur the Line Between Sci Fi and Reality

|

Jonathan Howard

Jonathan is a freelance writer living in Brooklyn, NY |

How could Lenovo have Missed Preloaded Superfish Adware’s Obvious Security Risk?

Superfish is probably the most annoying kind of invasive malware so why did Lenovo think it was going to go unnoticed? It’s actually worse than that. Lenovo claims they thought the Superfish software would be welcome and useful. If you aren’t a programmer or a web marketer you might not even understand what Superfish does at first glance. Basically, it can interject third party, paid advertising onto webpages that are otherwise encrypted. For example, you could have pop up ads or banner ads that weren’t sanctioned by your private bank show up on your online banking homepage. Adware of this nature breaks the usual http connections and can easily be exploited by anyone, not just advertisers who have a deal with Lenovo. Since Lenovo denied including the software on computers sold after December 2014, only to have indy security research personnel find Superfish on computers shipped after 2015, the scandal is going to creep among hackers, nerds and programmers while the rest of the world becomes that much less secure.

We have temporarily removed Superfish from our consumer systems until such time as Superfish is able to provide a software build that addresses these issues. As for units already in market, we have requested that Superfish auto-update a fix that addresses these issues.

Uh, yeah, temporarily removed, but does anyone even really want superfish on their Lenovo?

At first glance, Lenovo handled this issue in a professional manner as if it was all a big mistake. The further the software is discussed, dissected and examined, the less plausible the claim of an accidental security risk has become. Naturally, assurances from the dealer are not going to assuage fears completely, and rightly so, considering reports of computers having the software uninstalled, leaving elements of the code present to affect pop up ads and potentially leave the machine at risk. Serious damage to Lenovo’s rep aside, this is actually a big-picture win for consumers, who are seeing a hardware manufacturer backpedal out of a terrible move, hopefully setting precedent.

So what the heck was Superfish intended to actually DO?

Superfish is a “Visual Discovery browser add-on”, available on Lenovo consumer products excliusively. Superfish is uses an image search engine to supposedly help the user find products based on the appearance of said product. It does this by analyzing online images an markets identical and similar products in real time. The advantage is supposed to be that the user can search images while also being offered lower priced goods.

The software is cutting edge, searching 100% algorithmically without relying on text tags or human expeditors. If you show an interest in a product, superfish will already be hunting down a better deal. Lenovo insists:

Superfish technology is purely based on contextual/image and not behavioral. It does not profile nor monitor user behavior. It does not record user information. It does not know who the user is. Users are not tracked nor re-targeted. Every session is independent. When using Superfish for the first time, the user is presented the Terms of User and Privacy Policy, and has option not to accept these terms, i.e., Superfish is then disabled.

Yet, the visual search aspect of the program isn’t really dependant on Superfish’s disturbing ability to falsely sign security certificates. If it is a great search method and helps people find deals they didn’t ask for, that sounds cool yet annoying but is there any reason why it needs to see or interact with pages attempting to remain secure? Nope.

Because Lenovo has computers shipped to distributors with multiple methods of uninstalling the software, and some computers that were shipped before the uninstallation attempt, some machines still come with Superfish pre-installed. Lenovo had a rep post in a forum that Superfish has been uninstalled but had a shady excuse that there were “some issues (browser pop up behavior for example)” as the reason. Lenovo twitter account reiterated that the machines should be safe now. Regardless of their official stance via social media, it’s clearly still possible to buy Lenovo PCs that have superfish pre-installed. There has yet to be an update download from Lenovo or otherwise that can help get rid of the adware. Do PCs from other manufacturers pre-install Superfish or other invasive security risks, inadvertently or otherwise? Regardless, if you uninstall Superfish adware from your machines, a Superfish root certificate will remain, leaving your computer at risk to third party hacking.

World Cyberwar: Six Internet News Stories in 2015 Blur the Line Between Sci Fi and Reality

|

Jonathan Howard

Jonathan is a freelance writer living in Brooklyn, NY |

Are the Dark Ages Really in the Past? How an Internet Pioneer Thinks it Could Happen Again

The sound of the ‘Dark Ages’ conjures up a medieval nightmare of violent battles, unruly mobs and heretics, a bleak past that wasn’t necessarily as ominous or in the past as movies like to portray it – after all, there are a number of barbaric and superstitious people still alive today. The term was first used to describe the millennia between 500-1500 AD, a period from which there are few remaining historical records, or at least reliable ones. Consequently, we are often given a picture of the Middle Ages that is romanticized for better or worse, rather than accurate.

With the advent of computers and centuries of documents on microfiche it seems unlikely that such an incident will ever happen again, with an ocean of articles and pictures available at our fingertips. Unfortunately, one of the few people who can proudly rank himself among the founding fathers of the Internet, Vint Cerf, is not so optimistic, proposing a hypothetical nightmare scenario that programmers have talked about for many years: a Digital Dark Age, in which a wealth of written history may be lost, and with it so many things that we are dependent on computers for.

The twenty-first century alone has already presented several ways in which our data is in great peril, according to Cerf, and there is the possibility that it may be a century that hardly crosses anyone’s mind in the year 3000. In the near future, companies such as SpaceX are hoping to soon bring internet connections to higher speeds by moving wireless connections off the planet and into space by means of micro-satellites, where the inadequate speed of light is expected to cause inevitable delays in internet service. The ISS has already found evidence of both attainable high speed internet in space as well as resistance.

Cerf, one of Google’s vice presidents and one of the first to discover data packets, made waves at a recent convention of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, where he proposed that due to the rapid evolution of file formats, even in the event that our data survives, stored safely in our iCloud or elsewhere, we may accumulate a wealth of documents and files that we are unable to open because they are in formats that will rapidly become obsolete. Software continually updates and new versions may not always readily be able to read older files – a problem already exemplified by differences between WordPerfect and Microsoft Word, and not only applications but the machines themselves. Consider already the death of floppy disks, and the disappearance of CD and DVD drives from computers due to downloadable movies, another medium currently facing a format war. It’s a problem called backwards compatibility, something that upgrades of software do not always guarantee. As 2015 is already shaping up to be a much different place than 2005 was, a time when streaming video was just beginning to catch on, the technological difference from century to century could be vastly significant.

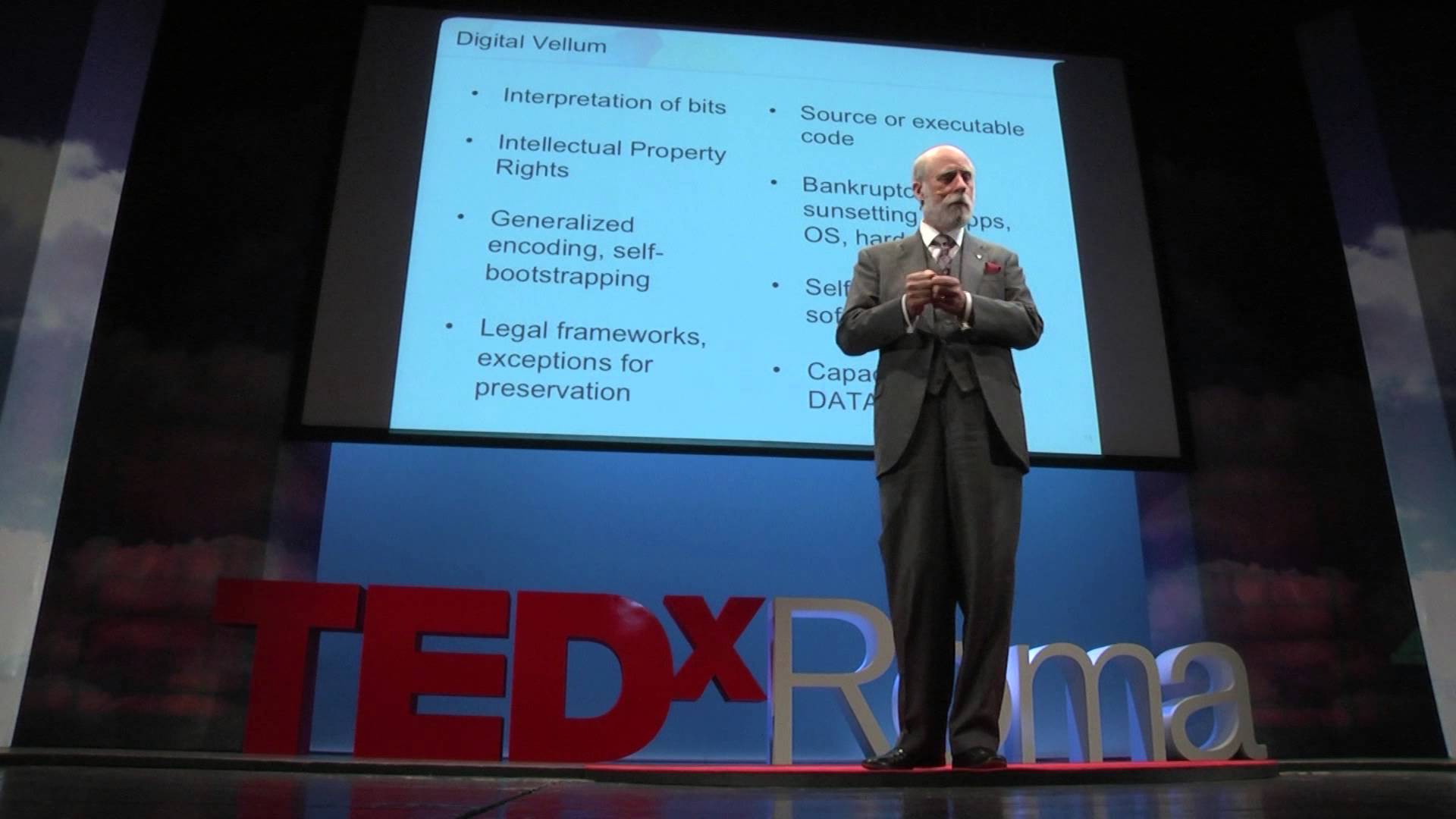

Fortunately, Cerf, who openly expressed a healthy skepticism over whether or not Google would still be around in the fourth millennium, is not all doom and gloom in his forecast. Already, he revealed the basics of a plan already demonstrated at Carnegie Mellon University, known as ‘digital vellum.’ Although the marketing concepts have not yet come to fruition, Cerf has left open the possibility that companies in the future may for a fee offer to create X-ray snapshots of all your digital files on a virtual machine that also replicates the operating system in which your data is stored – thus imitating Microsoft Office 97 if you had a Word file kept in that particular operating system.

While the logarithms have been established and discussed, the ethical concerns have yet to be addressed, a particularly prominent issue today as politicians continue to propose net neutrality laws and other regulations. When the internet is overwhelmingly protected by laws stemming out of legislation similar to SOPA or PIPA in the future, this too may complicate how we archive and access our data in the years to come. There is also the problem of intellectual property, which may prevent users from copying software and operating systems that are actively in use. There is also the issue of who can access the virtual machine copies, as technology may also end up having to be user specific, preventing the leakage of personal data.

|

James Sullivan

James Sullivan is the assistant editor of Brain World Magazine and a contributor to Truth Is Cool and OMNI Reboot. He can usually be found on TVTropes or RationalWiki when not exploiting life and science stories for another blog article. |

Can Information be Weaponized? Memetic Warfare and the Sixth Domain: Part Two

What role would optical illusions, graffiti and QR code technology play in weaponizing an image, sound, video or string of words to influence or control the human mind? Jonathan Howard takes a look at technology and the theoretical future of psychological warfare with the second part of an ongoing series. This installment of Can Information be Weaponized? is Memetic Warfare and the Sixth Domain: Part Two in which Jonathan Howard continues the train of thought about a possible delivery system for harmful memes by exploiting common mental weaknesses, including optical illusions, graffiti, and QR Code Technology. If you haven’t read it yet, you should start with Can Information be Weaponized? is Memetic Warfare and the Sixth Domain: Part One.

It’s an aspect of human psychology most readers will already be aware of: optical illusions. As Neil DeGrasse Tyson once pointed out, “an optical illusion is just brain failure”.

People like to trust their perception of what is happening in the world around them but there are circumstances where our perception of an image or set of images can’t be relied on as accurate. An illusion doesn’t have to be optical; we’ve all experienced an earworm, a piece of music, a movie quote or other form of recorded audio, which, once heard, seems to play with vivid realism. An earworm can make a sound seem to play on infinite repeat, often leaving the victim feel plagued by a sound that is not truly there.

Being fooled is a novelty and it can be fun but the video clip below demonstrates how illusions don’t just mess with your eyes(or ears). In certain, often common, circumstances illusory effects can actually modify the way your brain works. In January, 2014, vlogger Tom Scott created a recent video to explain the nature of the McCullough Effect, an optical illusion that can change the way your brain interprets colors in relation to striped patterns.

The video mentions the McCullough Effect can have lasting effects – potentially 3 months. In the interest of remaining unbiased I have not yet experimented but some Reddit users went ahead and tried it with believable results. Try it at your own risk~!

“You couldn’t rub out even half the ‘Fuck You’ signs in the world” ~ Holden Caulfield in J.D. Salinger’s A Catcher in the Rye

It would be difficult to weaponize the principle behind The McCullough Effect because the worm takes several minutes of intentional concentration to take effect. It’s a far cry from Medusa’s statue-creating gaze. Aspects of media can work much faster though. An offensive or upsetting image encountered via social media is often dubbed “cannot be unseen”. In J.D. Salinger’s A Catcher in the Rye, main character Holden Caulfield laments the human tendency to exploit written language with malice whenever he sees school kids exposed to vulgarity whenever a, “fuck you”, scrawled on a public wall. The illustration below illustrates this point by putting a gratuitous swearword in your head but has another possible harmful-meme delivery system: QR Code

Much in the way you can’t unsee a curse word written in a public space, a day may come when a more complicated curse-like state might be induced via QR code.

In February, 2014, Dr. Nik Thompson of Murdoch University pointed out QR codes can easily be exploited by cybercriminals because they can’t readily be interpreted by humans without the aid of a machine adding, “There have already been cases of QR codes used maliciously to install malware on devices, or direct them to questionable websites.”

Technically, by exploring the idea of exploited QR code, I’m making the same mistake as Diggins and Arizmendi, regarding compromised computer-assisted operating systems as a form of sixth domain warfare, when that would actually count as the fifth domain, cyber warfare. A compromised operating system on a phone or other smart device might seem like your brain is being attacked but the device is the only thing you’d be losing control of.

A truly weaponized piece of media might combine various elements of what I’ve described. Weaponized information would have to be:

- immediately absorbed like graffiti

- difficult or impossible to unsee like an offensive or disgusting image on the web

- able to induce or catalyze lasting changes in the mind like the McCullough Effect

- able to exploit the theoretical, bicameral firmware of the human mind as described in The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind(nonfiction) possibly in the manner of Snow Crash(fiction)

- possibly able to exploit the Fifth Domain of Warfare(Cyberspace) to reach the Sixth(The Mind) examples include human reliance on Brain-Computer Interface(BCI) is a major weakness in the modern human psyche, as described by Chloe Diggins and Clint Arizmendi or QR code Malware.

Thanks for reading Can Information be Weaponized? Memetic Warfare and the Sixth Domain: Part Two~! You can go back and read Part One here. Any suggestions, contradictions, likes, shares or comments are welcome.

Jonathan Howard posted this on Monday, February 9th, 2015

|

Jonathan Howard

Jonathan is a freelance writer living in Brooklyn, NY |

Can Information be Weaponized? Memetic Warfare and the Sixth Domain: Part One

Can an image, sound, video or string of words influence the human mind so strongly the mind is actually harmed or controlled? Cosmoso takes a look at technology and the theoretical future of psychological warfare with Part One of an ongoing series. This installment of Can Information be Weaponized? Memetic Warfare and the Sixth Domain: Part One is about a possible delivery system for harmful memes. You can click here to jump to Part Two.

Chloe Diggins and Clint Arizmendi wrote an article for Wired Magazine back in Dec., 2012 entitled, Hacking the Human Brain: The Next Domain of Warfare. The piece began:

It’s been fashionable in military circles to talk about cyberspace as a “fifth domain” for warfare, along with land, space, air and sea. But there’s a sixth and arguably more important warfighting domain emerging: the human brain. ~Hacking the Human Brain by Chloe Diggins and Clint Arizmendi, 2012, Wired Magazine

Hacking the Human Brain concentrated on the vulnerabilities of Brain-Computer Interface or BCI, giving some examples about how ever-increasing human reliance of computer-aided decision making in modern warfare opens users to security risks from weaponized hacking attempts. It’s a great article but the article is not actually discussing that sixth domain it claimed to in that opening paragraph I quoted above. The attacks described by Diggins and Arizmendi are in the nature of exosuits and mind-controlled drones being overridden by hackers, exhibiting the fifth domain of warfare of the given paradigm. What kind of attack would truly compromise, subjugate the sixth domain, the domain of the mind?

“Wait a minute, Juanita. Make up your mind. This Snow Crash thing—is it a virus, a drug, or a religion?”

Juanita shrugs. “What’s the difference?” ~ From Neil Stephenson’s Snow Crash, 1992

In Neil Stephenson‘s 1992 novel, Snow Crash, the hero unravels a complicated conspiracy to control minds using a complicated image file which taps into the innate, hardwired firmware language the human brain uses as an operating system. By simply viewing an image, any human could be susceptible to a contagious, self-replicating idea. The novel was ahead of its time in describing the power of media and the potential dangers posed by creating immersive, interactive virtual worlds and memes with harmful messages or ideas that can spread virally via social media. In the world of Snow Crash, a simple 2d image was the only technology needed to infect the human mind, forcing the victim to comply. The word and much of the concept of a meme had yet to be developed in 1992 but as the above quote points out, there are several, well tested mind control systems in existence already, including viruses, drugs and religions(Check out Snow Crash by Neil Stephenson at Amazon.com).

Stephenson waxed academic about language, history and the idea that ancient Sumerians had already uncovered this ability to hack the human mind. He later credited a 1976 book by Julian Jaynes, The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind as an influence and inspiration for Snow Crash. In Origin of Consciousness, Jaynes coined the term bicameralism, hypothetical psychological supposition that the human mind used to be divided into 2 main language functions. One part of the human mind was for speaking and the other was for listening, aka bicameralism. Jaynes claimed this state was normal in primates until a relatively recent change in language and cognition happened to humanity, supposedly about 3000 years ago. Stephenson’s fictional technology attacks modern man’s anthropologically latent compulsion to automatically accept orders when the orders are presented in the correct language.

Is a mind-control meme only the stuff of science fiction? In real life, how susceptible are humans to this kind of attack? Check out Can Information be Weaponized? Memetic Warfare and the Sixth Domain Part Two.

Thanks for reading Can Information be Weaponized? Memetic Warfare and the Sixth Domain: Part One~! Any suggestions, contradictions, likes, shares or comments are welcome.

Jonathan Howard posted this on Monday, February 9th, 2015

|

Jonathan Howard

Jonathan is a freelance writer living in Brooklyn, NY |

Quantum physics can fight fraud by making card verification unspoofable

By Boris Škorić, Eindhoven University of Technology

Decades of data security research have brought us highly reliable, standardized tools for common tasks such as digital signatures and encryption. But hackers are constantly working to crack data security innovations. Current credit/debit card technologies put personal money at risk because they’re vulnerable to fraud.

Physical security – which deals with anti-counterfeiting and the authentication of actual objects – is part of the problem too. The good guys and bad guys are locked in a never-ending arms race: one side develops objects and structures that are difficult to copy; the other side tries to copy them, and often succeeds.

But we think our new invention has the potential to leave the hackers behind. This innovative security measure uses the quantum properties of light to achieve fraud-proof authentication of objects.

PUFs: fighting with open visors

The arms race is fought in secret; revealing your technology helps the enemy. Consequently, nobody knows how secure a technology really is.

Remarkably, a recent development called Physical Unclonable Functions (PUFs) has made it possible to be completely open. A PUF is a piece of material that can be probed in many ways and that produces a complex response that depends very precisely on the challenge and the PUF’s internal structure.

The best known examples are Optical PUFs. The PUF is a piece of material – such as white paint with millions of nanoparticles – that will strongly scatter any light beamed at it. The light bounces around inside the paint, creating a unique pattern that can be used for authentication. Optical PUFs could be used on any object, but would be especially useful on credit/debit cards.

Chris Goldberg, CC BY-NC

Imagine presenting your card to an ATM. The ATM fires a laser beam at the white paint on the card. The beam has an intricate, unpredictable “shape” (angle, focus, pixel pattern) randomly generated by the ATM, which serves as the challenge. Inside the PUF, the light scatters many times, causing lots of interference.

The exiting light is the response – a complex pattern of dark and bright spots known as speckle that the ATM can record with a camera. The ATM has access to the PUF enrollment database and thus knows the properties of your card’s PUF when you insert it. The ATM computes what the reflected speckle pattern should look like. If the resemblance is close enough, the ATM considers the card authentic.

Speckle is sensitive to tiny changes in the challenge and the PUF’s structure. Due to the complexity of speckle physics, PUFs are practically unclonable.

The process for manufacturing PUFs does not have to be kept secret, precisely because of the unclonability: even if you know the manufacturing process, the uncontrollable randomness in the process still prevents you from cloning PUFs. One could organize open competitions and establish solid standards for physical security akin to those in cryptography.

Digital emulation still a problem

It’s conceivable a PUF could be cloned exactly, or physically emulated precisely, although it would be very, very difficult. With Optical PUFs the good guys are firmly on the winning side in the arms race.

A bigger risk for the authentication protocol is digital emulation. A digital emulation attack on a particular PUF would consist of three steps:

- First, a hacker measures the challenge. In the ATM example, this is the laser beam.

- Second, the hacker obtains the response to this challenge. This can be done either by looking it up in a previously compiled table, or by running emulation software. (Remember, the attacker knows everything about each PUF because this is public knowledge.)

- Third, the hacker sends out laser light with what he’s determined the correct “response” speckle pattern to be.

We are interested in “remote” authentication, where the verifier has no direct control over the PUF, and the attacker knows everything about the PUF. This scenario typically requires the verifier to put in the field heavily defended hardware devices (like ATMs), whose task is to read PUFs without being spoofed. But this opens a second type of arms race, namely designing secure electronics versus hardware hacking and spoofing. In this kind of game the “good guys” often find themselves on the losing side.

MESA+ Institute for Nanotechnology, Complex Photonic Systems Department of the University of Twente

Solution: Quantum Readout

A few years ago, I realized that using quantum physics in the PUF readout would completely eliminate the threat of digital emulation.

The challenge has to be an unpredictable quantum state – that is, a single photon – which then interacts with the PUF and returns as a modified quantum state. Instead of a “classical” speckle pattern as above, the verifier is looking for a lone photon in a particular complicated quantum state.

Due to the laws of quantum physics, an attacker cannot accurately determine what the challenge is. If the hacker tries to watch the photon, he collapses the quantum state – any attempt at measurement destroys most of the information. And the No Cloning Theorem says that it’s impossible to create an identical copy of a quantum state.

The attacker is out of luck. Not knowing the challenge, he doesn’t know where to look in his lookup table for a response. The verifier, on the other side, knows exactly which response is expected (in contrast to the attacker, he does know the challenge) and is able to determine if the returning photon is in the right state.

Though the security of the Quantum Readout concept has been rigorously proven, it was not immediately clear how to realize Quantum Readout in practice.

Manipulation of light

The funny thing about a photon is that it is both particle and wave. Since it is a particle you have to detect it as a single chunk of energy. And being a wave, it spreads out and interferes with itself, forming a speckle pattern response. Quantum light is like a complicated-looking ghost. But how do you verify a single-photon speckle pattern?

Boris Škorić, Author provided

In 2012, researchers at Twente University realized they held the answer in their hands. The magic ingredient is a Spatial Light Modulator (SLM), a programmable device that re-shapes the speckle pattern. In their experiments, they programmed an SLM such that the correct response from an Optical PUF gets concentrated and passes through a pinhole, where a photon detector notices the presence of the photon. An incorrect response, however, is transformed to a random speckle pattern that does not pass through the pinhole.

The method was dubbed Quantum-Secure Authentication (QSA).

Quantum, but not difficult

QSA does not require any secrets, so no money has to be spent on protecting them. QSA can be implemented with relatively simple technology that is already available. The PUF can be as simple as a layer of paint.

It turns out that the challenge does not have to be a single photon; a weak laser pulse suffices, as long as the number of photons in the pulse is small enough. Laser diodes, as found in CD players, are widely available and cheap. SLMs are already present in modern projectors. A sensitive photodiode or image sensor can serve as the photon detector.

With all these advantages, QSA has the potential to massively improve the security of cards and other physical credentials.

![]()

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Read the original article.

Satellites, mathematics and drones take down poachers in Africa

By Thomas Snitch, University of Maryland

In 2014, 1,215 rhinos were killed in South Africa for their horns, which end up in Asia as supposed cures for a variety of ailments. An estimated 30,000 African elephants were slaughtered last year for their tusks to be turned into trinkets. The world loses three rhinos a day and an elephant every 15 minutes. Simply stated, this is an unsustainable situation.

Our team at the University of Maryland’s Institute for Advanced Computer Studies has created a new multifaceted approach to combat poaching in Africa and Asia. We devise analytical models of how animals, poachers and rangers simultaneously move through space and time by combining high resolution satellite imagery with loads of big data – everything from moon phases, to weather, to previous poaching locations, to info from rhinos’ satellite ankle trackers – and then applying our own algorithms. We can predict where the key players are likely to be, so we can get smart about where to deploy rangers to best protect animals and thwart poachers.

The real game changer is our use of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) or drones, which we have been flying in Africa since May 2013. We’ve found that drones, combined with other more established technology tools, can greatly reduce poaching – but only in those areas where rangers on the ground are at the ready to use our data.

Thomas Snitch, CC BY-NC-ND

Scope of the problem

In the past 10 years, the poaching of elephants and rhinos has increased exponentially, primarily because it’s a very lucrative criminal business. Rhino horns can fetch more than US$500,000 or over $50,000 per kilogram – this is more than the cost of any illegal narcotic – and a pair of elephant tusks can reach US$125,000. Most of these illegal activities are run by Asian criminal syndicates and there are well-founded beliefs that some of these proceeds are being funneled to political extremists in Africa.

Being smart about deploying technology

Technology is a marvelous tool but it must be the right solution for a particular problem. Engineering solutions that might work with the US military looking for people planting IEDs in Afghanistan will not necessarily work in the African bush, at night, searching for poachers. The most challenging question about how UAVs are used in Africa is when and where to fly them.

Thomas Snitch, CC BY-NC-ND

Africa is too big to be simply launching small drones into the night sky with the hope of spotting rhinos or poachers by chance. This is where the analytical models come into play. Based on our models, we know, with near 90% certainty, where rhinos are likely to be on a particular night between 6:30 and 8:00, prime time for killings. At the same time, by mathematically recreating the environment when previous poachings have occurred, we have a very good idea of when and where poachers are likely to strike.

We don’t have to find poachers, we just need to know where the rhinos are likely to be.

For example, a large proportion of poachings occur on the days around a full moon; it makes sense since that’s when poachers can easily see their prey. In one area where we have months of experience, we discovered that nearly every poaching occurred with 160 meters of a road. It’s simple. The poachers are driving the perimeter of the park in the late afternoon spotting animals near the park fence; they return just after sundown, kill the animal and drive away. We pile on the data, and the algorithms do the rest.

Thomas Snitch, CC BY-NC-ND

Data informs on-the-ground rangers

The key is that the satellites, the analytics and math, and the UAVs are integrated into a solutions package. We crunch the data, and the model tells us precisely where we should deploy our rangers, on any specific night, so they will be in front of the rhinos and can intercept the poachers before they reach the target animal. After all, there’s no value in rangers patrolling parts of the park that these animals are unlikely to ever visit. Consider that South Africa’s Kruger National Park is the size of the state of New Jersey. Like a bank robber who robs banks because that’s where the money is, we want our rangers to be near the rhinos because that’s where the poaching is.

On our first UAV flight in South Africa, the UAV flew to our pre-determined spot and immediately found a female rhino and her calf; they were within 30 meters of a major road. We decided to circle the drone over the rhinos and within minutes a vehicle stopped at the park’s fence. Three individuals exited the car and began to climb the fence to kill the rhinos. Our rangers had been pre-deployed to the area; they arrested the three poachers in under 3 minutes. This episode has been repeated dozens of times over the past 20 months.

The most critical issue is not how far or how long a UAV can fly but how fast can a ranger be moved, in the bush at night, to successfully intercept poachers. The UAVs are simply our eyes in the night sky. Watching their live infrared video streams, we move our rangers as if they were chess pieces. Even with great math, we have some variance and that means we might be 200 meters off a perfect positioning. The UAVs can see poachers at least 2 kilometers from the rhinos. So we have 45 minutes to move our people into the most optimal position – based on our real world trials on how quickly they can move through the bush at night.

Thomas Snitch, CC BY-NC-ND

We’ve had hundreds of night flights with over 3,000 flight hours in the past 20 months and here is what we’ve learned. First, on the first few days after we begin operating in a new area, we arrest a number of poachers and they’re being prosecuted to the fullest extent of local laws.

Second, our models are heuristic in that they are constantly learning and self-correcting, on the lookout for changes in the patterns they’ve identified. This is critical since poachers will try to change their behavior once they learn that they are at an extremely high risk of apprehension. The sheer number of animals being killed shows us that, up until the UAVs take to the air, most poachers have been able to operate with impunity.

The most important finding is that in every area where we have put our solutions package to work and the UAVs are flying, poaching stops with 5 to 7 days. Period – it stops. Tonight we are flying in a very challenging area in southern Africa – we don’t identify our flight operations so as not to alert the poachers – and over the past 90 days, there has not been one single poaching incident. Four months ago, this region was losing several rhinos a week.

Thomas Snitch, CC BY-NC-ND

The good news is that we have proof of concept and proof on the ground that UAVS can make a tremendous difference. The bad news is that the poachers are moving to regions where we are not operating. To really address the challenges of poaching in the region, all the nations in southern Africa should be willing at least to test our system in their most critically endangered areas.

Our solution to the poaching problem lies in the combination of satellite monitoring, great math, properly positioned rangers and UAVS flying precise flight paths. It works.

![]()

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Read the original article.

How we can each fight cybercrime with smarter habits

Hackers gain access to computers and networks by exploiting the weaknesses in our cyber behaviors. Many attacks use simple phishing schemes – the hacker sends an email that appears to come from a trusted source, encouraging the recipient to click a seemingly innocuous hyperlink or attachment. Clicking will launch malware and open backdoors that can be used for nefarious actions: accessing a company’s network or serving as a virtual zombie for launching attacks on other computers and servers.

No one is safe from such attacks. Not companies at the forefront of technology such as Apple and Yahoo whose security flaws were recently exploited. Not even sophisticated national networks are home free; for instance, Israel’s was compromised using a phishing attack where an email purportedly from Shin Bet, Israel’s internal security service, with a phony PDF attachment, gave hackers remote access to its defense network.

To figure out why we fall for hackers’ tricks, I use them myself to see which kinds of attacks are successful and with whom. In my research, I simulate real attacks by sending different types of suspicious emails, friend-requests on social media, and links to spoofed websites to research subjects. Then I use a variety of direct, cognitive and psychological measures as well as unobtrusive behavioral measures to understand why individuals fall victim to such attacks.

What is apparent over the many simulations is how seemingly simple attacks, crafted with minimal sophistication, achieve a staggering victimization rate. As a case in point, merely incorporating the university’s logo and some brand markers to a phishing email resulted in close to 70% of the research subjects falling prey to the attack. Ultimately, the goal of my research is to figure out how best to teach the public to ward off these kinds of cyberattacks when they come up in their everyday lives.

Julia Wolf, CC BY-NC-SA

Clicking without thinking

Many of us fall for such deception because we misunderstand the risks of online actions. I call these our cyber-risk beliefs; and more often than not, I’ve found people’s risk beliefs are inaccurate. For instance, individuals mistakenly equate their inability to manipulate a PDF document with its inherent security, and quickly open such attachments. Similar flawed beliefs lead individuals to cavalierly open webpages and attachments on their mobile devices or on certain operating systems.

Compounding such beliefs are people’s email and social media habits. Habits are the brain’s way of automating repeatedly enacted, predictable behaviors. Over time, frequently checking email, social media feeds and messages becomes a routine. People grow unaware of when – and at times why – they perform these actions. Consequently, when in the groove, people click links or open attachments without much forethought. In fact, I’ve found certain Facebook habits – such as repeatedly checking newsfeeds, frequently posting status updates, along with maintaining a large Facebook friend network – to be the biggest predictor of whether they would accept a friend-request from a stranger and whether they would reveal personal information to that stranger.

Such habitual reactions are further catalyzed by the smartphones and tablets that most of us use. These devices foster quick and reactive responses to messages though widgets, apps and push notifications. Not only do smartphone screen sizes and compressed app layouts reduce the amount of detailed information visible, but many of us also use such devices while on the go, when our distraction further compromises our ability to detect deceptive emails.

These automated cyber routines and reactive responses are, in my opinion, the reasons why the current approach of training people to be vigilant about suspicious emails remains largely ineffective. Changing people’s media habits is the key to reducing the success of cyberattacks — and therein also lies an opportunity for all of us to help.

Harnessing habits to fight cybercrime

Emerging research suggests that the best way to correct a habit is to replace it with another, what writer Charles Duhigg calls a Keystone Habit. This is a simple positive action that could replace an existing pattern. For instance, people who wish to lose weight are instructed to exercise, reduce sugar intake, read food labels and count calories. Doing this many challenging things consistently is daunting and often people are too intimidated to even begin. Many people find greater success when they instead focus on one key attainable action, such as walking half a mile each day. Repeatedly accomplishing this simple goal feels good, builds confidence and encourages more cognitive assessments — processes that quickly snowball into massive change.

Martin Terber, CC BY

We could apply the same principle to improve cybersecurity by making it a keystone habit to report suspicious emails. After all, many people receive such emails. Some inadvertently fall for them, while many who are suspicious don’t. Clearly, if more of us were reporting our suspicions, many more breaches could be discovered and neutralized before they spread. We could transform the urge to click on something suspicious into a new habit: reporting the dubious email.

We need a centralized, national clearing house — perhaps an email address or phone number similar to the 911 emergency system — where anyone suspicious of a cyberthreat can quickly and effortlessly report it. This information could be collated regionally and tracked centrally, in the same way the Department of Health tracks public health and disease outbreaks.

Of course, we also need to make reporting suspicious cyber breaches gratifying, so people feel vested and receive something in return. Rather than simply collect emails, as is presently done by the many different institutions combating cyber threats, submissions could be vetted by a centralized cybersecurity team, who in addition to redressing the threat, would publicize how a person’s reporting helped thwart an attack. Reporting a cyber intrusion could become easy, fun, something we can all do. And more importantly, the mere act of habitually reporting our suspicions could in time lead to more cybersecurity consciousness among all of us.

This article is part of an ongoing series on cybersecurity. More articles will be published in the coming weeks.

![]()

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Read the original article.