Apple has the money and the know how… are they making your old iPhone suck through planned obsolescence just to force you into the checkout line for a new one?

Planned Obsolescence isn’t just a conspiracy theory. You can read the 1932 pamphlet, widely-considered the origin of the concept, here. The argument in favor of it is it’s effect on the economy; more products being produced and sold means an active, thriving market. Of course there is an obvious ethical problem of selling people a product that won’t continue to work as it should for as long as it should. Several companies openly admit they do it. For Apple, it works like this: Whenever a new iPhone comes out, the previous model gets buggy, slow and unreliable. Apple dumps money into a new, near perfect ad campaign and the entire first world and beyond irrationally feels silly for not already owning one, even before it’s available. Each release marks the more expensive iPhone with capabilities the last one can’t touch. This is already a great marketing plan and I’m not criticizing Apple’s ability to pull it off as described. The problem is planned obsolescence; some iPhone owners notice the older model craps out on them JUST as the newest iPhone hits the retail shops. Apple has the money and the know how… are they making your old iPhone suck just to force you into the checkout line for a new one?

Full disclosure, I’m biased: I owned an iphone for long enough to live through a new product release and mine did, indeed, crap out as described above. Slow, buggy, and unreliable it was. With that anecdote under my belt I might be satisfied to call this e-rumor totally true but in the interest of science I collected further evidence. I combed the messageboards to see who had good points and who is just the regular internet nutjob with a stupid theory. To examine the evidence, I’m gonna start with this fact:

Fact 1: Apple’s product announcements and new product releases come at regular intervals. So, if the old iPhones stop working correctly at that same interval there would be a coinciding pattern. The tricky part is finding the data but the pattern of release dates is a good place to start because it is so clear. Other companies could be doing this type of fuckery but it would be harder to track. Not only does Apple time their releases but they do it at a faster pace than most. The new iPhones tend to come out once a year but studies show people keep their phones for about 2-3 years if they are not prompted or coerced to purchase a newer model.

Fact 2: Yes, it’s possible. There are so many ways the company would be able to slow or disable last year’s iPhone. It could happen by an automatic download that can’t be opted out of, such as an “update” from the company. Apple can have iPhones come with pre-programmed software that can’t be accessed through any usual menu system on the iPhone. There can even be a hardware issue that decays or changes based on the average amount of use. There can be a combination of these methods. The thing is, so many people jailbreak iPhones, it seems like someone might be able to catch malicious software. There are some protocols that force updates, though. hmmm.

Fact 3: They’ve been accused of doing this every new release since iPhone 4 came out. his really doesn’t look like an accident, guys. This 2013 article in the New York Times Magazine by Catherine Rampell describes her personal anecdote, which, incidentally is exactly the same as the way my iPhone failed me. When Catherine contacted Apple tech support they informed her the iOS 7 platform didn’t work as well on the older phones, which lead her to wonder why the phones automatically updated the operating system upgrade in the first place.

Earlier on the timeline, Apple released iOS 4 offering features that were new and hot in 2010: features like tap-to-focus camera, multitasking and faster image loading. The iPhone 4 was the most popular phone in the country at the time but it suddenly didn’t work right, crashing and becoming too slow to be useful.

The iPhone 4 release made the iPhone 4 so horrible it was basically garbage, and Apple appeared to have realized the potential lost loyalty and toned it down. The pattern of buggy and slow products remained, though, When iOS 7 came out in 2013, it was a common complaint online and people started to feel very sure Apple was doing it on purpose.

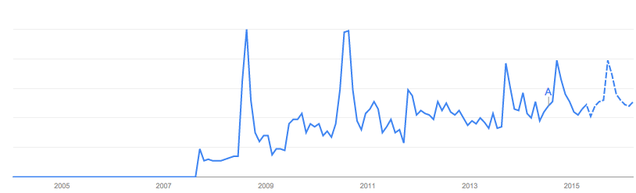

Fact 4: Google Trends shows telltale spikes in complaints that match up perfectly with the release dates. The New York Times(2014) called this one and published Google queries for “iphone slow” spike in traffic for that topic. Look at Google trends forecasting further spikes because the pattern is just that obvious:

Apple has a very loyal customer base, though. Rene Ritchie wrote for iMore, saying this planned obsolescence argument is “sensational,” and a campaign of “misinformation” by people who don’t actually understand how great an iPhone really is(barf). Even though the motive is crystal clear, the arguement that Apple is innocent isn’t complete nonsense, either: Apple ruining iPhones could damage customer loyalty. People espousing this argument claim an intentional slowdown is less likely than just regular incompatibility due to new software features. The latter point is a good one, considering how almost all software manufacturers have a hard time adjusting new software to old operating systems. Cooler software usually needs faster hardware and for some ridiculous reason no one has ever come out with an appropriately customizable smartphone and Apple woudl likely be the last on the list.

Christopher Mims pointed out on Quartz: “There is no smoking gun here, no incriminating memo,” of an intentional slowdown on Apple’s part.

There is really no reason to believe Apple would be against this kind of thing, even if planned obsolescence were a happy accident for the mega-corporation. Basically, if this is happening by accident it’s even better for Apple because they don’t have to take responsibility and it likely helps push the new line. Apple is far from deserving the trustworthy reputation they’ve cultivated under Steve Jobs, as the glitzy marketing plan behind the pointless new Apple Watch demonstrates.

|

Jonathan Howard

Jonathan is a freelance writer living in Brooklyn, NY |