How do humans interpret and understand art? The nature of artistic style, seemingly abstract and intuitive, is the subject of ongoing debate within art history and the philosophy of art.

When we talk about paintings, artistic style can refer to image features like the brushstrokes, contour and distribution of colors that painters employ, often implicitly, to construct their works. An artist’s style helps convey meaning and intent, and affects the aesthetic experience a user has when interacting with that artwork. Style also helps us identify and sometimes categorize their work, often placing it in the context of a specific period or place.

A new field of research aims to deepen, and even quantify, our understanding of this intangible quality. Inherently interdisciplinary, visual stylometry uses computational and statistical methods to calculate and compare these underlying image features in ways humans never could before. Instead of relying only on what our senses perceive, we can use these mathematical techniques to discover novel insights into artists and artworks.

A new way to see paintings

Quantifying artistic style can help us trace the cultural history of art as schools and artists influence each other through time, as well as authenticate unknown artworks or suspected forgeries and even attribute works that could be by more than one artist to a best matching artist. It can also show us how an artist’s style and approach changes over the course of a career.

Computer analysis of even previously well-studied images can yield new relationships that aren’t necessarily apparent to people, such as Gaugin’s printmaking methods. In fact, these techniques could actually help us discover how humans perceive artworks.

Art scholars believe that a strong indicator of an artist’s style is the use of color and how it varies across the different parts of a painting. Digital tools can aid this analysis.

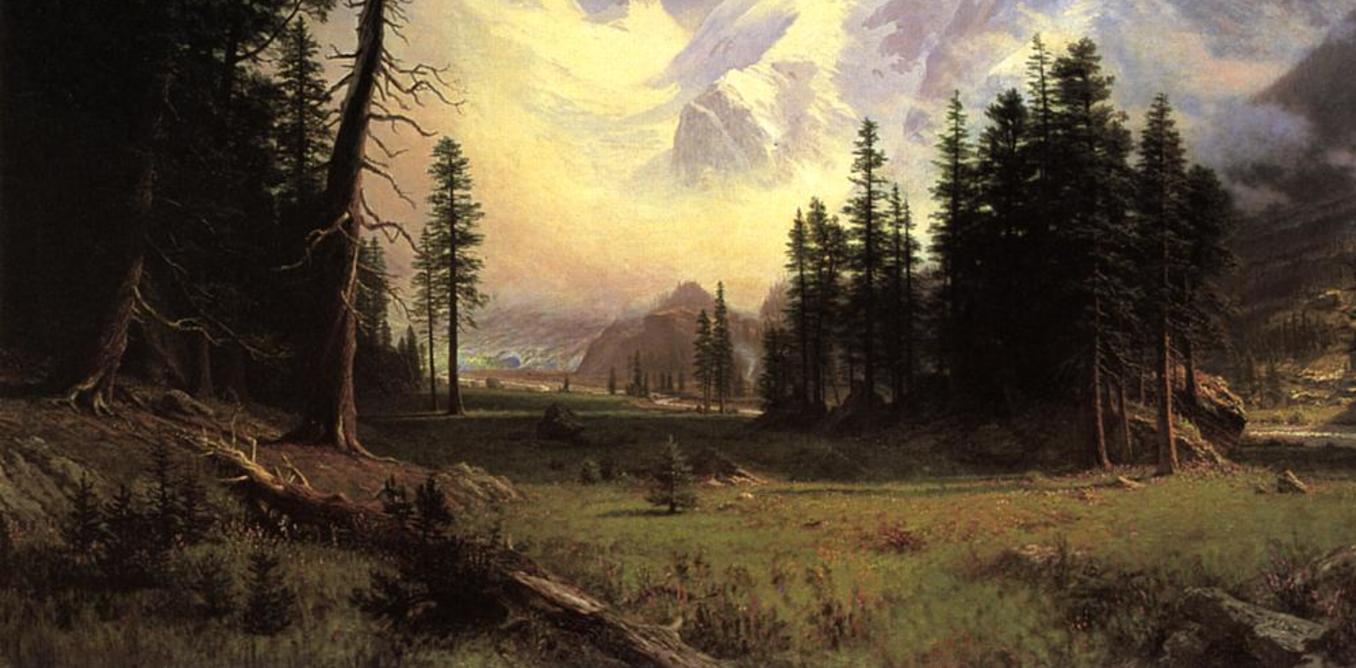

For example, we can start by digitizing a sample artwork, such as Albert Bierstadt’s “The Morteratsch Glacier, Upper Engadine Valley, Pontresina,” 1885, from the Brooklyn Museum.

Albert Bierstadt, 1895.

Wikiart

Scanning the image breaks it down into individual pixels with numeric values for how much red, green and blue is in each tiny section of the painting. Calculating the difference in those values between each pixel and the others near it, throughout the painting, shows us how these tonal features vary across the work. We can then represent those values graphically, giving us another view of the painting:

Author provided

This can help us start to categorize the style of an artist as using greater or fewer textural components, for example. When we did this as part of an analysis of many paintings in the Impressionist and Hudson River schools, our system could sort each painting by school based on its tonal distribution.

We might wonder if the background of a painting more strongly reflects the artist’s style. We can extract that section alone and examine its specific tonal features:

Author provided

Then we could compare analyses, for example, of the painting as a whole against only its background or foreground. From our data on Impressionist and Hudson River paintings, our system was able to identify individual artists – and it did so better when examining foregrounds and backgrounds separately, rather than when analyzing whole paintings.

Sharing the ability to analyze art

Despite the effectiveness of these sorts of computational techniques at discerning artistic style, they are relatively rarely used by scholars of the humanities. Often that’s because researchers and students don’t have the requisite computer programming and machine-learning skills. Until recently, artists and art historians without those skills, and who did not have access to computer scientists, simply had to do without these methods to help them analyze their collections.

Our team, consisting of experts in computer science, the philosophy of art and cognitive science, is developing a digital image analysis tool for studying paintings in this new way. This tool, called Workflows for Analysis of Images and Visual Stylometry (WAIVS), will allow students and researchers in many disciplines, even those without significant computer skills, to analyze works of art for research, as well as for art appreciation.

WAIVS, built upon the Wings workflow system, allows users to construct analyses in the same way they would draw a flowchart. For instance, to compare the tonal analyses of the whole painting and the background alone, as described above, a scholar need not create complex computer software, but rather would just create this design of the process:

Author provided

The diagram is actually a computer program, so once the user designs the workflow, they can simply click a button to conduct the analysis. WAIVS includes not just discrete tonal analysis but other image-analysis algorithms, including the latest computer vision and artistic style algorithms.

Another example: neural algorithm of artistic style

Recent work by Leon Gatys and others at the University of Tübingen, Germany, has demonstrated the use of deep learning techniques and technology to create images in the style of the great masters like Van Gogh and Picasso.

The specific deep learning approach, called convolutional neural networks, learns to separate the content of a painting from its style. The content of a painting consists of objects, shapes and their arrangements but usually does not depend upon the use of colors, textures and other aspects of artistic style.

A painting’s style, extracted in this manner, cannot be viewed on its own: it is purely mathematical in nature. But it can be visualized by applying the extracted style to the content of another painting or photo, making an image by one artist look like it’s by someone else.

Our group has incorporated these techniques into WAIVS and, as we add more cutting-edge algorithms, art scholars will be able to apply the latest research to their analyses, using our simple workflows. For example, we were able to use WAIVS to recreate the Bierstadt painting in other artists’ styles:

Author provided

Connecting disciplines

Eventually, we intend to incorporate WAIVS within a Beam+ telepresence system to allow people to virtually visit real-world museum displays. People around the world could not only view the art but also be able to run our digital analyses. It would dramatically expand public and scholarly access to this new method of contemplating art, and open new avenues for teaching and research.

Our hope is that WAIVS will not only improve access of humanities researchers to computerized tools, but also promote technological literacy and data analysis skills among humanities students. In addition, we expect it to introduce science students to research in art and the humanities, to explore the nature of artistic style and its role in our understanding of artwork. We also hope it will help researchers in cognitive science understand how viewers perceptually categorize, recognize and otherwise engage with art.

![]()

Ricky J. Sethi, Assistant Professor of Computer Science, Fitchburg State University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.