On May 11 the Obama admin released updated guidance on insurance coverage of contraception. The announcement provides much-needed clarification for insurance plans regulated by the Affordable Care Act (ACA).

Before this announcement, the guidance for what insurers were supposed to do was vague.

The ACA requires insurers to provide women access to the full range of FDA-approved contraceptive methods at no cost. But insurers could use “reasonable medical management” to introduce cost-containment measures like providing generics at no-cost, while requiring co-pays for a branded equivalent.

Some insurers used reasonable medical management to restrict access to some forms of contraception – often the more expensive, but longer-lasting forms. And that lead to variation among insurance plans about which contraceptives required a co-pay and which did not.

The new guidance specifies that at least one birth control method from each of 18 different categories must be covered without cost-sharing in all eligible plans. Reasonable medical management and cost-containment strategies can still be used, as long as methods in each category are offered.

So why does it matter than some insurers were restricting access to some forms of contraception?

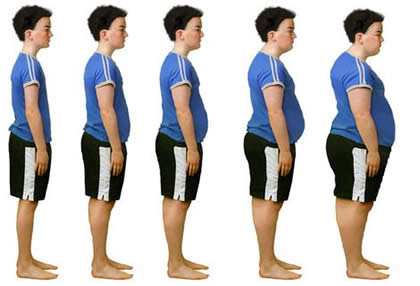

About half of pregnancies in the US are unintended – and that has much to do with access and use of contraception. Unintended pregnancies lead to an estimated US$5 billion in costs for the US health-care system per year, while birth control use provides cost-savings of $19 billion each year. Even small improvements in contraceptive use could result in a meaningful reduction in the number of unintended pregnancies.

Why are co-pays such an important issue?

Relative to other forms of health care, the low cost of so many contraceptive methods may make the individual out-of-pocket expense seem unimportant. But to many women, these costs are real. Cost is a big factor in choosing to use one form of contraception over another, using it consistently or even the likelihood of using contraception at all.

Notably, the most effective methods (such as long-acting reversible contraceptives, like intrauterine devices (IUDs) or hormone implants) have the highest up-front cost. And if women must share the cost, that discourages them from using these highly effective methods.

We studied the relationship between out-of-pocket costs and contraception use among almost 1.7 million women enrolled in the types of plans regulated by the ACA rules between January 1 and December 31, 2011. Women in plans with the highest level of cost-sharing were 35% less likely to have an IUD placed than women with the lowest level of cost-sharing – suggesting that even higher income women are sensitive to the price of contraceptives.

The Contraceptive Choice study, which offered almost 10,000 women free birth control, demonstrated that low-income and uninsured women will select the most effective (and most expensive) birth control methods at high rates when cost is not a factor.

This is why the new White House guidelines are so important. The broader menu of options available will increase women’s access to their preferred method, which may in turn improve contraception use patterns and decrease unintended pregnancy.

Contraceptive pills via www.shutterstock.com.

One contraceptive is not like another

All contraceptives aim to prevent pregnancy, but there are a variety of ways they can do so. They aren’t interchangeable and the method that may work best for one woman may not be suitable for another.

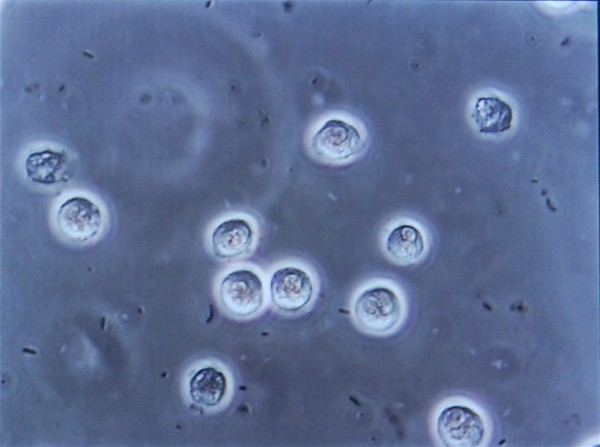

Under previous guidance, many insurers interpreted the law to mean they must cover at least one – but not all – option from each of five categories: hormonal contraception (like birth control pills, vaginal rings or patches), barrier methods (diaphragm), emergency contraception, implanted devices (like IUDs or hormone implants) and sterilization.

But this approach to grouping methods doesn’t reflect the clinical uses for each type of contraception. For instance, the contraceptive ring was considered a “hormonal” method, and since there is a generic pill containing the same hormones as the ring, insurers have often not covered it because they consider them equivalent. But the ring lasts for three weeks before needing to be replaced, while the pill needs to be taken every day. And this distinction is important for women who know that they will sometimes forget to take a pill every day.

Even methods that are similar – such as the copper IUD and the hormone-containing IUD – are not, in medical parlance, therapeutic equivalents. This means that they have different medical uses, health benefits or side effects. These products aren’t interchangeable – the best one for an individual woman will depend on her menstrual patterns, tolerance of side effects and prior birth control experience. Clinicians, therefore, use them in different situations

When physicians help women choose the “best” choice, we look at her medical history, lifestyle and a product’s unique characteristics. In contraception, it’s important to never underestimate the importance of side effects or ease of use, since they can drive how consistently a woman uses a particular method. If our goal is consistent, effective use, we must remove barriers to an individual’s choice of birth control method.

Pills and IUD via www.shutterstock.com.

How much of a difference will the new guidelines make?

In the months before the White House released the new guidelines, three different reports captured the coverage variations between insurance plans.

A report from the Guttmacher Institute, a non-profit organization focused on reproductive health, in September 2014 found that women continued to report out-of-pocket costs, especially for the most effective methods, like the IUD.

In April, a report from the Kaiser Family Foundation looked at coverage for 12 contraceptive methods among 20 different insurance carriers in five states. The organization found significant variation in interpretation and coverage among the plans. They also found that methods such as the vaginal ring and patch (which don’t need to be taken daily) and the most-effective methods like the implant and IUD, were less likely to be covered without cost-sharing.

Further gaps were identified by the National Women’s Law Center in an analysis of more than 100 insurance plans in 15 states. They concluded that 33 plans in 13 states did not comply with the ACA. These plans were not covering all FDA-approved methods. They imposed cost-sharing, only covering generic methods or were not covering associated services, such as counseling or administration visits.

If our nation wishes to reduce the high number of unintended pregnancies – and the costs and abortions that result from them – improving women’s access to the contraceptive methods they prefer, and that they will use consistently, is key. The updated guidelines from the White House mean that American women face fewer barriers to use the contraceptive method of their choice.

![]()

Vanessa K Dalton is Associate Professor at University of Michigan.

Lauren MacAfee is Fellow, Family Planning at University of Michigan.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Read the original article.