Up to one in six animal and plant species could vanish from the face of the Earth as casualties of climate change, according to the latest analysis.

Up to one in six animal and plant species could vanish from the face of the Earth as casualties of climate change, according to the latest analysis.

The new study was published on Thursday with the journal Science. If that’s hard news to take, it might get even worse. Mark Urban, who is an ecologist from the University of Connecticut, also suspects that as our planet continues to warm up over the rest of the century, the rate of extinction among species will likely begin to accelerate. The presence of most of these animals is necessary for their habitats to remain stable.

“We have the choice,” he warned in a recent interview. “The world can decide where on that curve they want the future Earth to be.”

As severe as these conclusions made by Dr. Urban’s may be, his estimate appears conservative compared to some other counts taken by his colleagues. The precise number of extinctions “may well be two to three times higher,” according to John J. Wiens, who is an evolutionary biologist at the University of Arizona.

Trends of anthropogenic global warming have increased our planet’s average surface temperature by an average of about 1.5 degrees Fahrenheit since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, a primary reason that modern geologists have lobbied to change the name of the modern geological record to the Anthropocene Era. People forming societies have not only left a permanent mark on the planet, but have also influenced the evolution and even extinctions of an immeasurable number of species. In response to climate change, many animals have begun shifting their habitats, where they face fresh competition in a new and already established ecosystem.

Back in 2003, Camille Parmesan from the University of Texas alongside Gary Yohe from Wesleyan University decided to analyze the published studies of more than 1,700 different species of plants and animals. They subsequently learned that, on an average, the ranges of these animals have shifted over 3.8 miles each decade towards one of the planet’s poles, another unfortunate side effect of climate change that biologists are currently dealing with.

If these emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases – such as the much more lethal methane – continue to increase in our atmosphere, climate researchers maintain that the world may warm by as much as a full eight degrees Fahrenheit. As the Earth’s climate continues to intensify, as scientists fear, a number of these species will no longer be able to establish suitable habitats to sustain life.

The American pika, is one such example. These are hamster-like mammals found on mountain ranges throughout the West. In recent years, however, they have been climbing to higher elevations to build their nests. Since the 1990s, some established pika populations living throughout their southernmost ranges have entirely vanished, a loss that may upset the balance of nature in minute ways that will eventually become more pronounced – predators in the area no longer have pikas as a food source, and regional grasses they used for their nests may now grow unchecked.

Hundreds of studies have come out over the course of the last two decades, all of which have released quite a host of predictions about the number of extinctions that may be the result of global warming. So many have entertained the possibility of a mass extinction, that some naturalists have suggested we are living in what will be the sixth major extinction event, with the depletion of many species over the next two million years. Some have predicted few extinctions, while others have maintained that up to 50 percent of the Earth’s species will be eradicated with the planet’s mounting temperatures.

So why is there such a wide variation? The main reason is because all of these studies take different lifeforms into account. Some scientists have focused their efforts solely on plants throughout the Amazon, whereas other researchers concentrated on butterfly species in Canada. In some of these cases, the researchers applied models that considered only a couple of degrees of warming whereas other studies looked into significantly hotter scenarios. Because the scientists were rarely able to give estimates on how quickly one given species might alter its ranges, in some cases they decided to produce a range of estimates.

In order to establish a clearer picture, Dr. Urban decided he would need to look into every climate extinction model that has ever published. He eliminated any studies in which just a single species was examined, such as reports on the American pika, in order to avoid the possibility that his numbers might end up overly inflated. Studies that look at just one species generally imply that the species in question is already in danger of dying out from climates change.

Dr. Urban ended up doing his analysis on 131 different studies examining plants, amphibians, fish, mammals, reptiles and invertebrates, all of which are spread widely across the planet. His study reanalyzed all of their data.

Overall, Urban found that there are 7.9 percent of the world’s species highly vulnerable to becoming extinct from reasons related to climate change. The estimates which factored low levels of warming yielded significantly less extinctions than the hotter scenarios.

According to his calculation, all it would take is an increase of 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit of just the planet’s surface temperature, and 5.2 percent of species could become extinct. At an increase of 7.7 degrees, 16 percent of species would disappear.

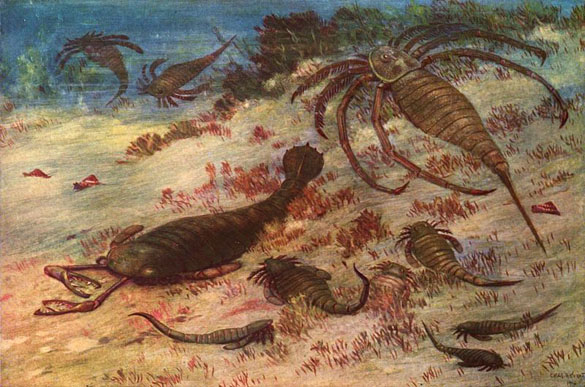

Dr. Urban’s model has projected that this rate of extinctions will not increase steadily, but could actually accelerate if temperatures rose. This could mean not just a mass extinction event, but one that may be on par with the Permian Triassic Extinction, in which 90 percent of life on Earth died out, over a period of just 60,000 years – the deadliest event the planet has ever known. Ocean acidification, a growing concern over the last century, has been established as playing a major role in the Permian Triassic event.

Richard Pearson, a biogeographer from University College London, has referred to the latest meta-analysis as “an important line in the sand that tells us we know enough to see climate change as a major threat to biodiversity and ecosystems.”

But, even Pearson maintained that Dr. Urban is most likely underestimating the exact scale of species extinctions. We tend to think of extinctions as a one day cataclysmic event, but the reality is that they take substantial amounts of time, during which habitats diminish and new populations of other animals are introduced. The latest generation of climate extinction models are more accurate, according to Dr. Pearson: “Sadly, they also produce more dire estimates.”

Dr. Wiens also takes note that the tropics have long been underrepresented when doing climate extinction studies, likely because they probably contain large numbers of species that have not yet been discovered, and the margins of errors are considerable. In Dr. Urban’s meta-analysis of the studies, 78 of them focused on animals living throughout North America and Europe, while there were only seven that came from South America, home of the most unusual and rapidly disappearing ecosystem in the world: the Amazon River basin. However, even when Dr. Urban did a combination of all the data acquired from these South American studies, he learned that approximately 23 percent of species on this continent were at a high vulnerability to extinction. In North America, by comparison, only 5 percent of the species were threatened with extinction.

“What makes this imbalance all the more glaring,” Dr. Wiens said, “is the fact that most of the planet’s species live in tropical forests such as the Amazon. If climate extinction research took tropical diversity into account, the planet’s overall risk would be much higher.” Not only animal life, but much of the Amazon’s plants are specially adapted to the region.

Dr. Urban, however, has acknowledged that his meta-analysis is far from the final word, and hopes that other researchers will continue to pursue the totality of species extinctions, as well as the best possible methods for counting them out. “This is a summary of the best information we have right now,” he said. “As the predictions improve, they will allow conservation biologists to pinpoint the species at greatest risk of extinction and help plan strategies to save them.”

The scientists who create subsequent models may actually be able to draw not only from the data we have on living species, but also from extinct ones as well. How the loss of one species is felt by another is an important question to bear in mind.

In an issue of Science this week, an international team of researchers reported a new and rather unsettling find regarding the nature of ocean extinctions over the last 23 million years.

They discovered that particular groups, such as sea mammals, are actually much more prone to extinctions than other groups whose ancestors reach back several ages, such as the mollusks. Biology can help determine how certain species are put at extra risk. For example, in the case of sea mammals, such extinct species as the Steller’s Sea Cow, they typically produce fewer offspring, giving the species lower odds for survival. Other animals may have a limited range, such as modern day amphibians, which are falling victim to fungal diseases and dying off from the loss of their habitats.

Dr. Pearson has said that in the future, climate extinction models have new factors that they will also need to take into account. “What happens to other species in an ecosystem when a species goes extinct?” he asked. “Its partners in that habitat might risk extinction as well.”

Dr. Urban is also aware that there are many other ways in which scientists can improve climate extinction models. A big thing they should seek to do in the future is calculate the increase of human interaction. Humans too have been forced to migrate due to changes in climate, a problem that will unlikely change in the near future – leading to increases in the populations of cities, but also the need for expanding farms as well as other barriers that humans have set for those species who seek new habitats. Giant salamanders in Asia, for example, have had their habitats disrupted from the establishment of hydroelectric plants in local streams, and are at high risk.

The startling results of his research so far, indicates that new and improved prediction models can’t come too late. “We need to elevate our game,” said Urban.

|

James Sullivan

James Sullivan is the assistant editor of Brain World Magazine and a contributor to Truth Is Cool and OMNI Reboot. He can usually be found on TVTropes or RationalWiki when not exploiting life and science stories for another blog article. |