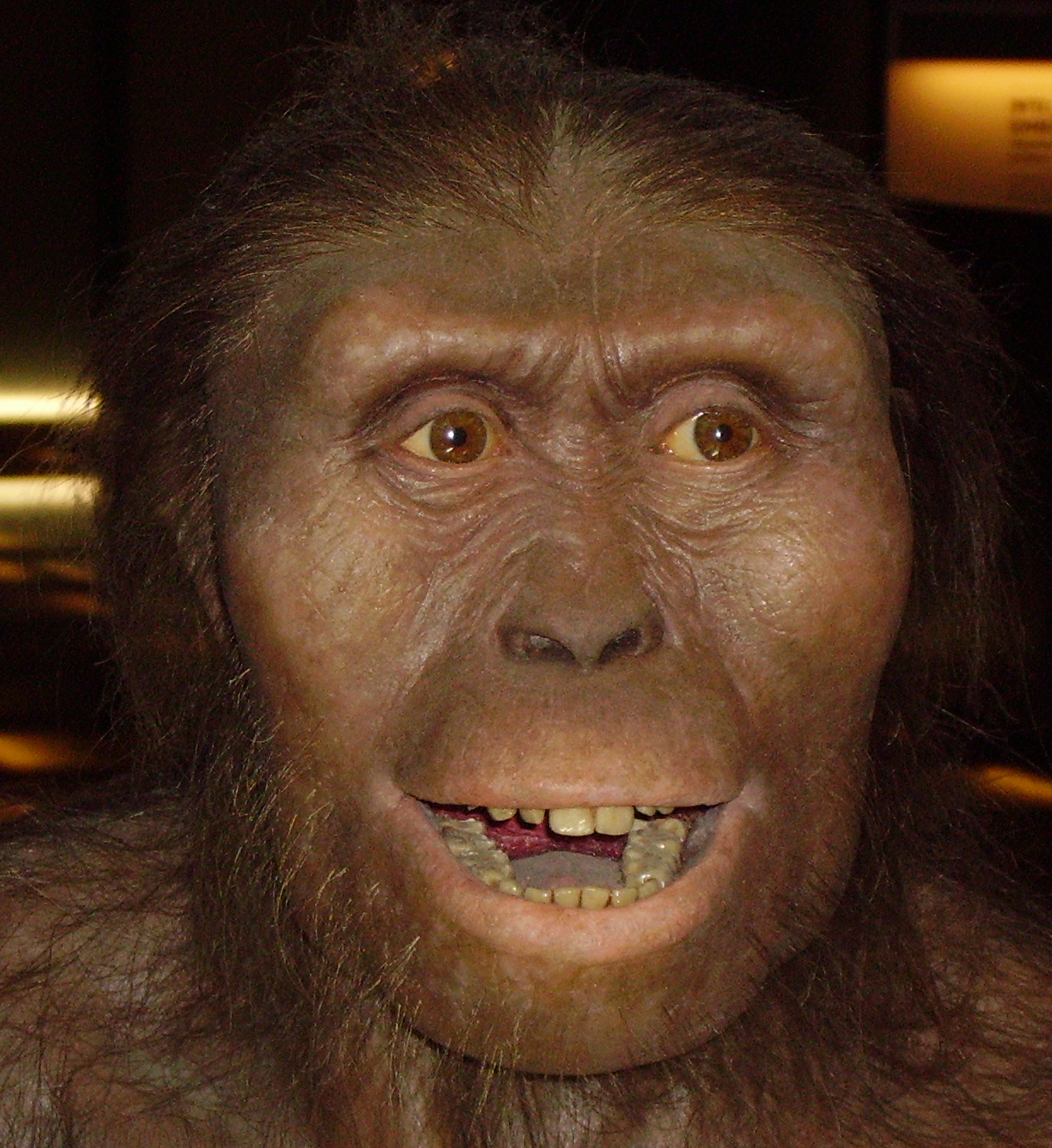

Deep in Ethiopia’s Awash Valley about four decades ago, paleontologists came very close to understanding the origin of modern humans when they unearthed Australopithecus afarensis, better known as Lucy, an upright walking ape that lived about 3.2 million years ago, one of our distant ancestors. Now we know that Lucy wasn’t alone – sharing the savannah with another ape-like creature that scientists refer to as “Little Foot,” suggesting a rich evolutionary diversity throughout much of Africa at the time.

The date of the fossil is important for another reason – it may give us a closer approximation to when modern day humans first began to appear. Currently, Australopithecines are ranking high among the species believed to be our direct ancestors, living in Africa between 2.9 million and 4.1 million years ago. The exact lineage from which we came, Homo, dates back to approximately two million years ago.

Although the Australopithecus afarensis thrived in the grasslands of eastern Africa, another australopithecine nicknamed Little Foot, due to the diminutive nature of the bones, lived in southern Africa. Discovered about 20 years ago by paleoanthropologist Ronald Clarke from the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa, Little Foot apparently fell down a narrow shaft in the Sterkfontein Caves. This left behind a nearly complete skeleton that could yield key insights on human evolution.

So what sort of australopithecine was Little Foot? There are about five different varieties known, and also the sub tribes of hominins Paranthropus and Ardipithecus which had comparable brain sizes and walked on two legs. A number of scientists think that Little Foot likely belonged to the genus Australopithecus africanus, which differed from Lucy in that it had a rounder skull used to contain a slightly larger brain and smaller teeth than Lucy or much else of Australopithecus afarensis. Now Clarke and his colleagues have proposed the idea that perhaps Little Foot may have been another type of australopithecine – the Australopithecus prometheus, which was characterized by a longer and flatter face as well as larger cheek teeth than the Australopithecus africanus.

“It was impossible to fit Little Foot into the human family tree with any certainty because ever since its discovery, the age of Little Foot has been debated,” according to the study’s lead author Darryl Granger, who is a geochronologist at Purdue University of West Lafayette, Indiana. If the researchers are able to determine successfully when Little Foot’s family tree first came into being, they might then be able to make a more accurate distinction of when Australopithecus first diverged, as well as which region of Africa the Homo genus first originated in.

While most paleoanthropologists agree that the first hominins, as well as all of the modern human race, have ancestral roots in Africa, it is difficult to pinpoint a precise starting point, since a rapidly changing climate drove them across the continent and gradually towards the Middle East and European mainland.

The evidence discovered by Granger and his colleagues has suggested that Little Foot lived at approximately the same time as Lucy, but the current fossilized remains are not yet sufficient enough to determine what species it belonged to.

“The most important implication from dating Little Foot is that we now know that australopithecines were in South Africa early in their evolution,” Granger told Live Science. “This implies an evolutionary connection between South Africa and East Africa prior to the age of Little Foot, and with enough time for the australopithecine species to diverge.”

This proposes another issue that many have not considered, however – other australopithecines — and, eventually, humans, such as Neanderthals and Homo Sapiens, “did not all have to have derived from Australopithecus afarensis,” Clarke told Live Science. “There could well have been many species of Australopithecusextending over a much wider area of Africa.”

The researchers made their first attempt at determining the age of Little Foot a little over a decade ago. Their result was an age of around four million years, which according to Granger, would rank Little Foot among the oldest of the australopithecines. Despite the fact that they looked a lot more like apes than humans (our closest living relative the chimpanzee quickly comes to mind), Australopithecines did show some signs of being human – the fossil record shows they cared for their children much like modern humans, and they may have had a sense of aesthetic. Some of their dwellings contained stones that resembled faces, collected from nearby valleys.

You might wonder how they can date materials discovered within a cave, which can prove to be another frustrating problem for archaeologists. Besides being able to determine if they’re from the same era as the remains found within the cave, there is also the problem of erosion that could cause unearthed materials to fill a cave along with water currents and sediments, something that could easily throw off most types of analysis. Such mineral rich runoff is known as flowstones when found in caves. The initial step taken by archaeologists was to date this material, which revealed an age of 2.2 million years old. “I was disappointed, but I could see nothing wrong with their ages,” Granger recalled.

A recent study suggested the flaw with this method – as the flowstones formed at a different time than the rock layer containing the fossils. For their newest analysis, Granger and colleagues were able to determine the age of the fossils with by analyzing the aluminum and beryllium isotopes in quartz found in the same layer, a technique known as surface exposure dating, which can give dates on mineral materials that are up to 30 million years old.

The researchers came across something else surprising – the earliest stone tools that they discovered within the same cave only date back about 2.2 million years ago. This gives them an age similar to the early stone tools discovered throughout eastern and southern Africa, indicating that there must have been some degree of interaction between their later descendants. “This implies a connection between South African and East African hominids that occurred soon after the appearance of stone tools,” Granger said.

The researchers hope that their new dating method will be used by other archaeological sites across the globe. will “There should be a thorough study to explore the strengths and weaknesses of the method,” Granger said.

The findings made by Granger, Clarke and their research team were documented and published in the April 2 issue of the journal Nature.

|

James Sullivan

James Sullivan is the assistant editor of Brain World Magazine and a contributor to Truth Is Cool and OMNI Reboot. He can usually be found on TVTropes or RationalWiki when not exploiting life and science stories for another blog article. |