Over the last decade, there’s been quite a debate about whether or not, and perhaps more importantly whether or not we should, clone the woolly mammoth back to life. So far, researchers have made some progress on the first question at least. Back in 2005, the Mammoth Creation Project suggested that a creature with 88 percent resemblance to extinct species of mammoth could be cloned successfully within the next 50 years. Already, they may have their first major breakthrough in the processes of cloning.

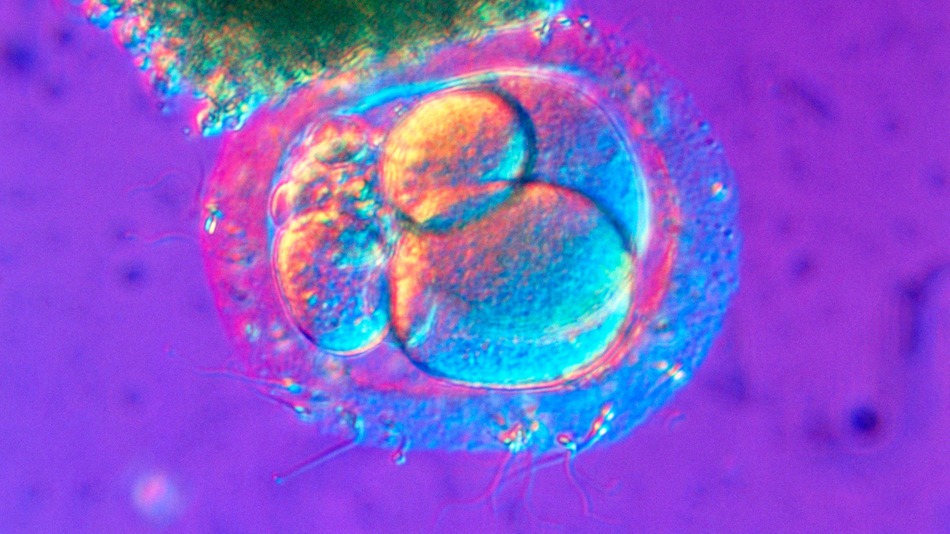

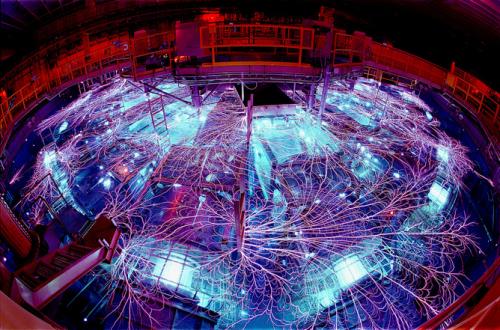

One of the most prominent geneticists in the United States has successfully managed to extract DNA out of the frozen remains of a frozen mammoth discovered at Wrangel Island in the Arctic Ocean. Although the original strands of DNA are long dead, there was enough genetic information on the animal, which was well preserved with skin and hair, to build a synthetic replica which they then implanted inside the cells of an Indian Elephant – the mammoth’s closest living relatives, which are also about the same size. The elephant cells were kept isolated inside a petri dish. With the aid of a revolutionary (and somewhat controversial) DNA splicing technique known as CRISPR that allows for unprecedented accuracy, which allows for editing genes and even spreading them to the next generation. Lead researcher George Church, of Harvard University, has proudly reported that so far the cells are doing quite well.

The woolly mammoth died out some 10,000 years ago on the mainland in North America, roughly two millennia after mammoth species died out in Europe. The smaller ones indigenous to Wrangel Island, however, lived on peacefully without our intervention until about 1650 BC, overlapping with the rise of civilization in ancient Egypt and the construction of the oldest pyramids at Giza. Before then, they had dominated the Earth for 250,000 years during the Pleistocene Age, thriving during the last of Earth’s five major ice ages, when the planet was between nine and eighteen degrees Fahrenheit colder than it is today. This climate is the primary reason that mammoths, mummified under layers of snow and ice are so easy to find in prime condition, particularly as the Siberian permafrost thaws. Some have even revealed what their fur looked like. So plentiful were the carcasses at one point, that the 1951 Explorers’ Club’s annual dinner in Manhattan actually offered small morsels of mammoth meat for appetizers.

As temperatures became warmer and sea levels began to rise once again, life became a bit harder for the woolly mammoth, particularly around 18,000 years ago, when tribes of hunter-gatherers grew bigger and more organized, successfully hunting them down in large numbers. While Church and his team of researchers were not yet able to fully replicate a complete woolly mammoth genome so what they did was make copies of the genes responsible for the ‘mammoth-like’ attributes that we know – like heavy layers of fat to protect against the cold climate, the ears, which are actually shorter than the ones on modern elephants, tusks, and heavy coats of fur.

“We prioritised genes associated with cold resistance including hairiness, ear size, subcutaneous fat and, especially haemoglobin,” Church revealed to Ben Webster of The Sunday Times. Hemoglobin may have been the key genetic ingredient in helping mammoths tolerate extreme winters. Regardless of the temperature, this protein managed to keep oxygen traveling to the muscles at a constant speed, and may have allowed the mammoths to develop cooling systems for their limbs. By comparison, the hemoglobin in modern elephants, like humans, functions better in warm weather.

While there are samples of flesh and hair that would seem like natural reservoirs for DNA, the trouble is that the meat that has been found is thoroughly rotten, and while the fur shows an orange color, paleontologists have had to adjust the colors they’ve found for what may have been damage to the pigments from being trapped for so long under the ice. Another problem is that many of the mammoths born later clearly suffered birth defects. Cervical ribs that appear in some of the later females may have led to reproductive stress, joining overhunting and climate change as a possibility for their gradual decline.

While people have certainly played at least a partial role in the animal’s disappearance, our technology may eventually bring them back. According to Church: “We now have functioning elephant cells with mammoth DNA in them. We have not published it in a scientific journal because there is more work to do, but we plan to do so.” If successful, we may soon see the first mammoth in nearly 3,300 years.

The technique that combines elephant DNA with the extinct mammoth genome is CRISPR/Cas9, which has lately been used to develop transgenic organisms with an impressive track record. This marks the first time, however, that the technology has taken on the DNA of an extinct organism.

The researchers will next work to determine the best way to reproduce their work with elephant cells outside of the petri dish. It’s actually quite a tall order, but if they are somehow able to this with the use of elephant eggs, then they just might be able to program an elephant that will grow up to be just like a woolly mammoth. The question, however, is whether doing so would be a good idea. De-extinction is a point of contention among many researchers. Not all of them are quite enthusiastic about the idea. According to biologist Alex Greenwood from the Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research, in an interview with The Telegraph:

“We face the potential extinction of African and Asian elephants. Why bring back another elephantid from extinction when we cannot even keep the ones that are not extinct around? What is the message? We can be as irresponsible with the environment as we want. Then we’ll just clone things back?

Money would be better spent focusing on conserving what we do have than spending it on an animal that has been extinct for thousands of years.”

He certainly raises some good points. There are only a few rhinoceroses and a continuously declining population of iconic wildlife throughout Africa, elephants and even the predators like lions suffering from disease. The woolly mammoth would be returning to the world, entering an ecosystem that has adapted to thousands of years of life without them, and require a specialized diet. If we’re already having problems with spreading populations of invasive species, then bringing back extinct species might create an entirely new headache.

On the other hand, many grasslands in North America are showing the impact of having lost their larger grazers such as the megatherium (a bear-sized sloth), 18,000 years after the fact. Perhaps there is the promise of some ecological stability taking place, or perhaps further cultivating the mammoth genome may lead to further improvements in the technology of gene editing. If not an extinct species, perhaps this experiment might also lead to focusing on the preservation of species that only recently died out or those currently extinct in the wild, such as the black rhinoceros. We might be too late in having a thorough debate on the matter anyway, as Church’s team is only one of three research teams in the world actively at work on bringing back the woolly mammoth, but the fact that the issue has been raised alone is important, if only for bringing to the table new ways to preserve already endangered species.

|

|

James Sullivan

James Sullivan is the assistant editor of Brain World Magazine and a contributor to Truth Is Cool and OMNI Reboot. He can usually be found on TVTropes or RationalWiki when not exploiting life and science stories for another blog article.

|