If you are reading this and you don’t smoke, then your major risk factor for dying is probably your age. That’s because we have nearly eliminated mortality in early life, thanks to advances in science and engineering. But despite this progress, we still haven’t worked out how to eliminate the damaging effects of ageing itself.

Now a new study in mice, published in Nature, reveals that stem cells (a type of cell that can develop into many other types) in a specific area of the brain regulate ageing. The team even managed to slow down and speed up the ageing process by transplanting or deleting stem cells in the region.

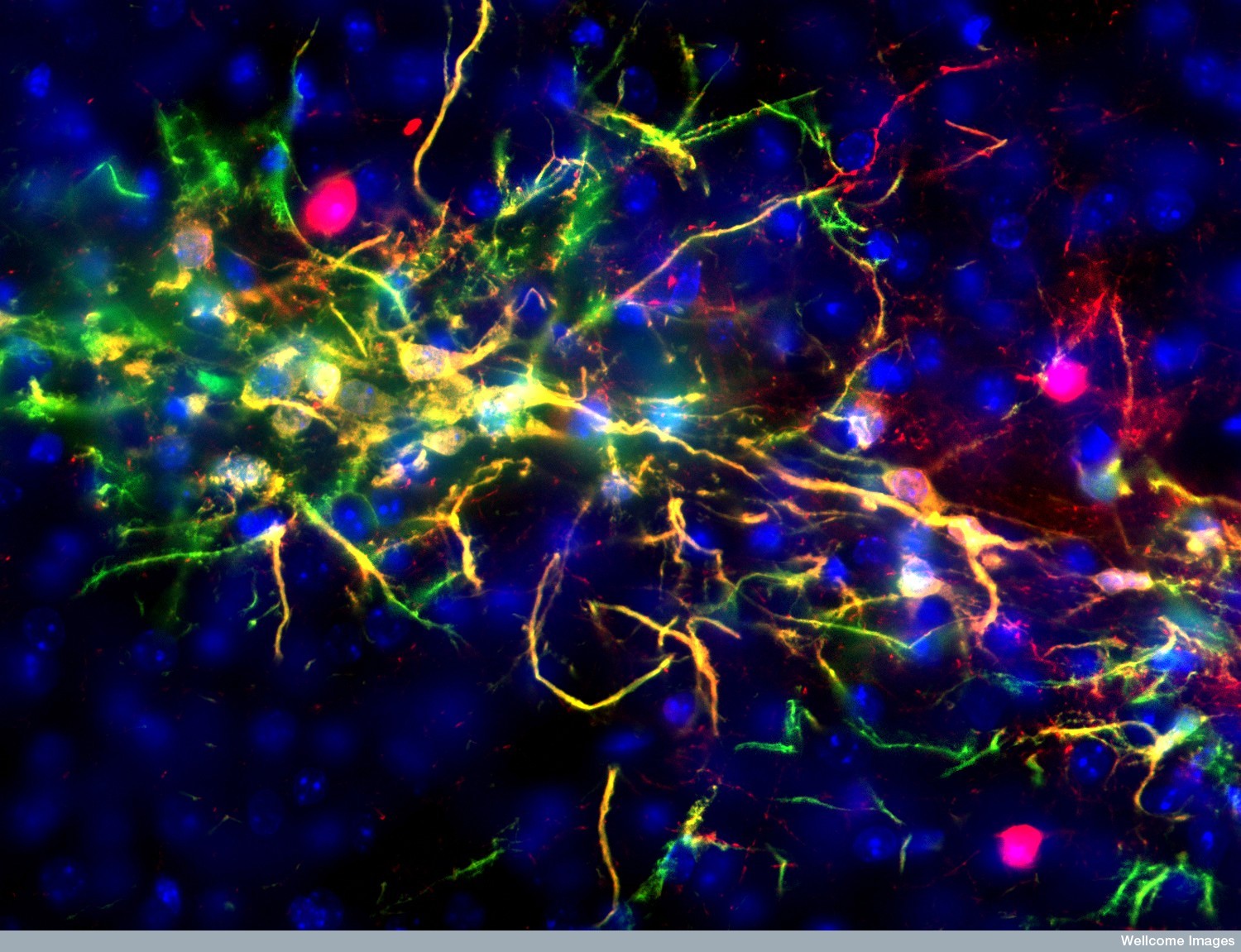

from www.shutterstock.com

Ageing poses an important challenge for society. By 2050, there will be as many old people (age 65+) as children (under 15) on Earth for the first time. This change is reflected in unprecedented stress on our health and social care systems. Understanding how we can keep ourselves in good health as we age is becoming increasingly important.

The mechanisms that keep organisms healthy are relatively few in number and conserved between species, which means we can learn a lot about them by studying animals such as mice. Among the most important are senescent cells – dysfunctional cells which build up as we age and cause damage to tissue – chronic inflammation and exhaustion of stem cells. These mechanisms are thought to be connected at the cell and tissue level. As with a ring of dominoes, a fall anywhere can trigger a catastrophic collapse.

Vanishing cells

The researchers behind the new paper were studying the mouse hypothalamus, which we’ve known for some time controls ageing. This almond-sized structure at the centre of the brain links the nervous and endocrine (hormone) systems. The hypothalamus helps regulate many basic needs and behaviours including hunger, sleep, fear and aggression. In the human brain, initiation of behaviours is usually complex, but if you flee in blind panic or find yourself in a blazing rage, then your hypothalamus is temporarily in the driving seat.

The team looked at a specialised group of stem cells within the hypothalamus and monitored what happened to them as cohorts of mice aged. Mice normally live for about two years but they found that these cells began to disappear by about 11 months. By 22 months, they had vanished completely. The rate at which the stem cells was lost closely correlated with ageing changes in the animals, such as declines in learning, memory, sociability, muscle endurance and athletic performance.

But correlation doesn’t mean causation. To find out if the decline was causing these ageing changes, they deleted stem cells using a specially engineered virus that would only kill them in the presence of the drug Ganciclovir. In 15-month-old mice, receiving this drug combination destroyed 70% of their hypothalamic stem cells. They prematurely displayed signs of ageing and died roughly 200 days earlier as a result. That’s significant as mice only live for about 730 days.

The group also implanted hypothalamic stem cells from newborn mice into middle-aged animals. In this case, the animals became more social, performed better cognitively and lived about 200 days longer than they otherwise would have.

These experiments also provided clues to how the hypothalamic stem cells were being lost in the first place. The implantation only worked when the stem cells had been genetically engineered to be resistant to inflammation. It seems that, as the animals aged, chronic, low-grade inflammation in the hypothalamus increased.

This inflammation is probably caused either by the accumulation of senescent cells or surrounding neurons entering a senescent-like state. Inflammation kills the hypothalamic stem cells because they are the most sensitive to damage. This then disrupts the function of the hypothalamus with knock-on effects throughout the organism. And so the dominoes fall.

Elixir of youth?

The ultimate goal of ageing research is identifying pharmaceutical targets or lifestyle interventions that improve human health in later life. While this is a study in mice, if we can show that the same mechanisms are at play in humans we might one day be able to use a similar technique to improve health in later life. But this remains a long way in the future.

Other interventions, such as removing senescent cells, also improve health, extending life by up to 180 days in mice. A logical next step is to see if these interventions “stack”.

Evgeny Atamanenko

The study also demonstrates that hypothalamic stem cells exert major effects through secreting miRNAs, which control many aspects of how cells function. MiRNAs are short, non-coding RNAs – a molecule that is simpler than DNA but can also encode information. When miRNAs were supplied alone to mice lacking stem cells they actually showed similar improvements to those who received stem-cell treatment.

The delivery of miRNAs as drugs is still in its infancy but the study suggests potential routes to replenishing a hypothalamus denuded of stem cells: preventing their loss in the first place by controlling the inflammation. This might be achieved either through the development of drugs which kill senescent cells or the use of anti-inflammatory compounds.

The research is important because it elegantly demonstrates how different health maintenance mechanisms interact. However, one downside is that only male mice were used. It is well known that the structure of the hypothalamus differs markedly between the sexes. Drugs and mutations which extend lifespan also usually show markedly different potency between males and females.

![]() Whether humans will ever be able to live significantly longer than the current maximum lifespan of 125 years is hard to tell. But it seems the greatest barrier to a healthy later life is no longer the rate of progress but the speed with which we can turn our growing knowledge of the biology of ageing into drugs and lifestyle advice.

Whether humans will ever be able to live significantly longer than the current maximum lifespan of 125 years is hard to tell. But it seems the greatest barrier to a healthy later life is no longer the rate of progress but the speed with which we can turn our growing knowledge of the biology of ageing into drugs and lifestyle advice.

Richard Faragher, Professor of Biogerontology, University of Brighton

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.