In what may be a memorably controversial and groundbreaking new research paper, scientists from China describe in detail the way in which they were successful at manipulating the genomes, or genetic blueprints of human embryos for what is the first time in human history, reintroducing all new ethical concerns about what just may be the next frontier for science.

The story was first reported by Nature News this Wednesday, and their paper was originally published by a little known online journal called Protein and Cell.

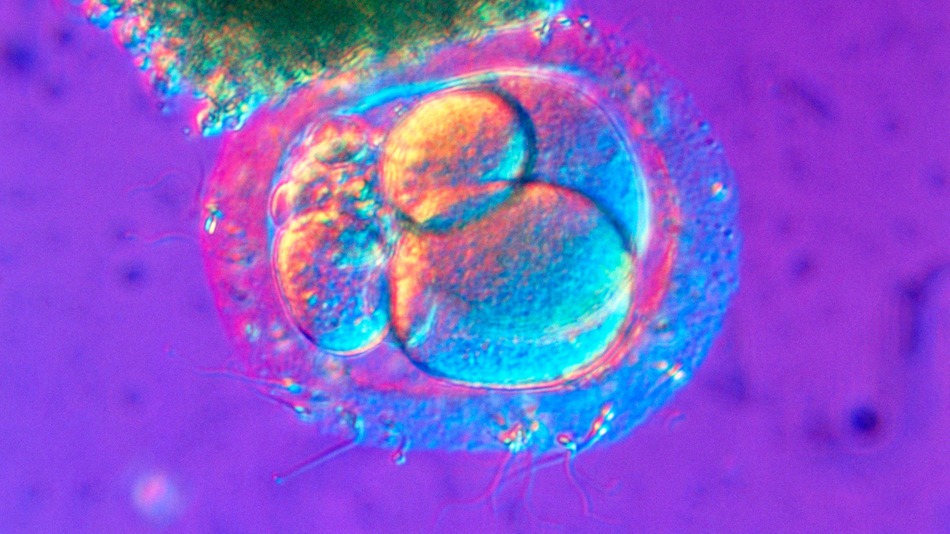

In their paper, Junjiu Huang, who is a gene-function researcher from Sun Yat-sen University of Guangzhou, and his colleagues describe the way in which they edited the genomes from embryos they received from a fertility clinic.

The embryos were described as non-viable in the paper, ones that would not be capable of resulting in a live birth because a genetic replication error resulted in them containing an extra set of chromosomes from being fertilized by two different sperm.

The researchers “attempted to modify the gene responsible for beta-thalassaemia, a potentially fatal blood disorder, using a gene-editing technique known as CRISPR/Cas9,” according to the report from Nature News.

“The researchers say that their results reveal serious obstacles to using the method in medical applications.”

The researchers injected the CRISPR into 86 different embryos and then they waited another 48 hours for the molecules that would replace any missing DNA to begin their work.

71 of the embryos survived, and 54 out of that number were then tested.

Researchers learned that just 28 of the embryos had been “successfully spliced, and that just a small fraction of these successes contained the necessary replacement genetic material,” read the report.

“If you want to do it in normal embryos, you need to be close to 100 percent,” Huang said in a statement to Nature News.

“That’s why we stopped. We still think it’s too immature.”

What was more concerning, however, is that there were a “surprising number” of unintended mutations that occurred during the process, and accelerating at a speed that was far higher than anything seen in earlier gene-editing studies which used either mice or adult human cells.

Such mutations, moving at an unchecked speed, could be harmful, and they are one of the primary reasons for why people in the scientific community are expressly concerned. It’s a worry that grew when rumors of Huang’s research team began to circulate at the beginning of the year.

“It underlines what we said before: we need to pause this research and make sure we have a broad based discussion about which direction we’re going here,” said Edward Lanphier, president of Sangamo BioSciences in Richmond, California, in an interview with Nature News.

While the gene editing technique has shown some unprecedented success, there is the question of what effect rapid rates of mutation may have – bringing to light some potential disorders that the scientific community is not yet aware of.

George Daley, who is a stem-cell biologist at Harvard Medical School of Boston, Massachusetts, was careful in his praise of the research, describing it as “a landmark, as well as a cautionary tale.”

“Their study should be a stern warning to any practitioner who thinks the technology is ready for testing to eradicate disease genes,” he said to Nature News.

More studies may be coming to light soon. So far, there are rumors of at least four other Chinese research teams also actively working on human embryos, according to the report.

|

James Sullivan

James Sullivan is the assistant editor of Brain World Magazine and a contributor to Truth Is Cool and OMNI Reboot. He can usually be found on TVTropes or RationalWiki when not exploiting life and science stories for another blog article. |