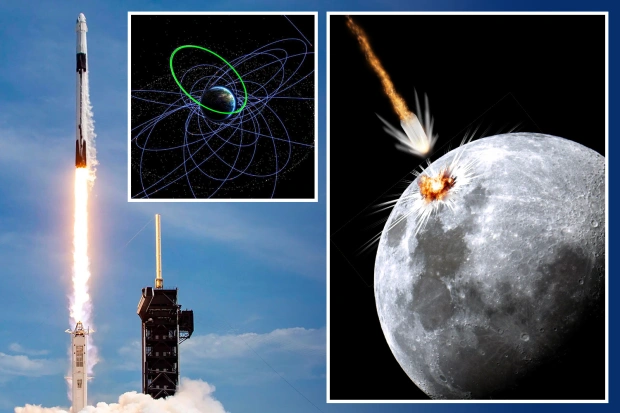

It’s not clear where a SpaceX rocket will crash into the moon, but observers think it will likely hit the lunar equator in a few weeks. This isn’t the first time a rocket has crashed into the moon. Last February, SpaceX launched a booster into orbit that launched a mission to Mars. The booster performed a long burn and deployed a NOAA space station, but did not have enough fuel to return to Earth.

Scientists believe that a SpaceX rocket will crash into the moon on March 4, 2019. This is because it’s a near-Earth object, which means that it will crash into the moon. However, there is a small chance that it will change its trajectory after the launch, affecting the exact impact spot. Amateur astronomers have calculated that the upper stage of the rocket has been in orbit for seven years, and this will influence the exact time of the crater formation.

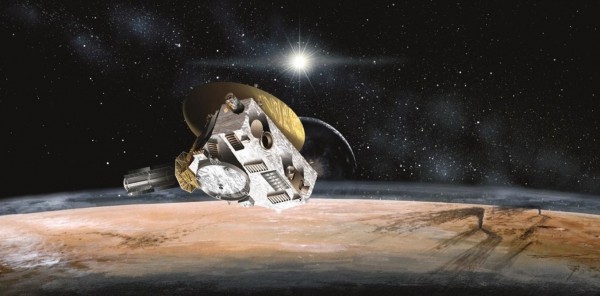

The crater will be large enough to bury a spacecraft. The rocket’s four-ton booster will crash into the lunar surface at about 5,600 mph, which will probably create a crater several feet wide. NASA’s LCROSS spacecraft purposely crashed into the moon in 2009, and collected data about the impact. This impending SpaceX crash will give astronomers the opportunity to study crater formation on the moon.

The exact timing of the crater’s impact remains uncertain, but the impact will occur on March 4 and will cause the moon to be impacted by the booster. The exact location remains uncertain because of the unpredictability of the moon’s gravity. Nevertheless, NASA is planning to send astronauts back to the Moon by 2025, which is far sooner than most people believe. This event will be a milestone in space exploration.

In March, the second stage of a Falcon 9 rocket will crash into the moon at a speed of 1.6 miles per second. The moon is a dark object and will be darkened by the impact. The space junk is increasing at a staggering rate, and this will accelerate the second space race. The Apollo-Ariana mission was the first to land on the Moon, but its mission ended in disaster in the skies.

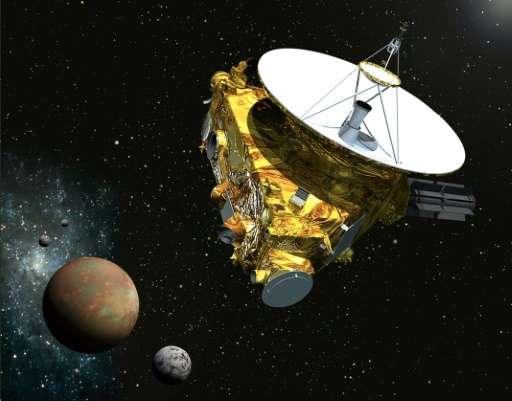

The astronomical impact will happen near the equator of the moon on March 4. The SpaceX rocket is on a collision course with the moon seven years after it was launched. In addition to the lunar impact, the spacecraft will hit the Earth seven months later, on the day when the equator is closest to the moon. The crash, however, will be visible only to a few space-watchers.

The first SpaceX rocket will crash into the moon on 7 February. It will be visible from Earth until the moon’s surface is too dark to see the impact. This mission will be a historic moment for humans as the first ever in the history of astrophysics. In February 2015, Elon Musk’s rocket was attempting to launch a weather satellite. The runaway part of the rocket failed to return to Earth’s orbit and instead headed to the moon.

The space rocket’s second stage is set to crash into the moon on March 4. While the impact is unlikely to affect Earth or human life, the new crater may reveal some interesting information about the composition of the moon. The company didn’t immediately respond to an ABC News request for comment on the crash. There is still a small window of time in the lunar orbit for the rocket to reach the moon. It is expected to hit the moon at a high-speed and should impact at a low-speed.

Although the impact isn’t a major event, scientists are still working to determine the exact time of the crash. While the rocket will not hit the moon directly, the second stage’s impact should occur at a speed of 2.58 kilometres per second. It is expected to cause no damage to Earth and no human life, but it is still a huge milestone for science. The collision is a significant milestone for humankind.