There have been growing concerns in the global health care system about the eradication of pathogens in hospitals and other patient-care environments. Overuse of antibiotics and antimicrobial agents has contributed to the emergence of antibiotic-resistant superbugs – such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE) – which are difficult to kill. Lower immunity of sick patients coupled with the escalating problem of antibiotic-resistant pathogens has driven increased rates of infection in hospital and surgical environments.

It’s become crucially important to find ways to control infection in these settings. My research has focused on ways we can do so using alternative antibacterial materials such as the heavy metal silver. I’ve been working on a technique that electrically activates silver to create an antimicrobial surface. We can use this technology to create touch-contact and work surfaces – for instance, door knobs, push plates, countertops – that would help control the transmission of infections, primarily in health care environments. And now we’re experimenting with using silver in medical implants.

Silver takes the gold in fighting bacteria

Silver has long been known for its antibacterial properties. A variety of medical products including ointments, bandages, surgical tools and catheters employ silver-based technologies to prevent or fight infection.

But just an inert lump of silver isn’t going to do much. To be effective, it must first ionize. Research has shown that it’s silver in its ionic (Ag+) and not elemental form that is antibacterial. An atom of silver has a neutral charge; we need to ionize it – take away a negatively charged electron – to transform it into its positively charged ionic form. Silver-based antibacterial surfaces must release silver ions directly into the pathogenic environment to be effective.

Silver ions have antibacterial properties for a few reasons. They can interfere with with cell DNA and affect their ability to procreate. They can inhibit enzymes involved with respiration, essentially suffocating the bacteria cells. And they can react with sensitive thiol groups on bacterial proteins to destroy normal biological activity of the protein. The multi-modal activity also makes it difficult for bacteria to develop resistance in the same way they do to specific antibiotic medications.

Taking silver to inner space

Particularly with our aging population, the number of joint replacement surgeries is growing in the US. And with more surgeries, the associated risks of infection go up too. Now my work with my student George Tan is focused on taking the bacteria-fighting power of silver ions inside the body.

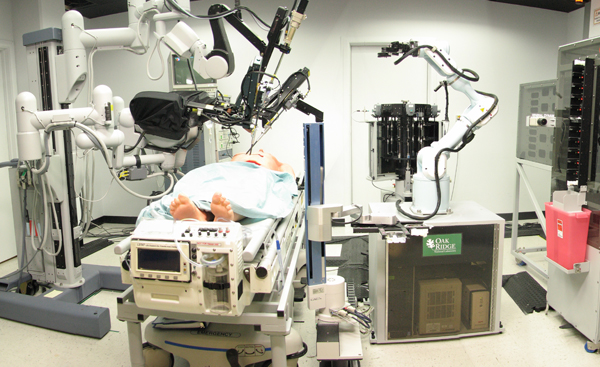

Rohan Shirwaiker, CC BY-NC-ND

We are engineering ways to apply a low-intensity electrical charge to a silver-titanium orthopedic implant. Our technique releases silver ions that kill or neutralize bacteria on and around the implant. The power source, which could be a strong watch battery, can potentially be integrated into the implant design. The body’s own fluids act as a conducting medium between the titanium and silver, enabling the low-level electrical current necessary to create and release the silver ions into the environment which might contain pathogens.

Rohan Shirwaiker, CC BY-NC-ND

This technology has the potential to dramatically reduce infections which negatively affect patient health, quality of life and health care costs. Our in vitro lab testing has shown a 99% decrease in bacteria growth on and around implants after 24 hours and an infection-free environment after 48 hours.

One of the engineering challenges is to precisely control the level of silver that is released so that no healthy cells are compromised; silver can be toxic. In future, we may explore the possibility of a smartphone app to control the power source and the release of silver ions remotely. Perhaps we could also devise a way to track the biophysical activity around the implant area. Broad application of the system could result in a significant advancement in the fight against infection, with the potential to be incorporated into any type of surgical implant.

Infection continues to be a major complication associated with implantable devices. Although rates vary, an average annual infection rate of approximately 5% (at least 100,000 cases/year) associated with orthopedic procedures involving fracture fixation devices and joint prostheses costs the US healthcare system over $1.5 billion annually. Treatment may require surgical procedures including implant removal, debridement of infected tissue, implant replacement and 6–12 weeks of antimicrobial therapy. Innovations in silver microbial technology could eventually have a wide-ranging impact on patient outcomes as well as on the health of the medical economy.

![]()

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Read the original article.