Mirrors out perform most modern image technologies in terms of resolution, efficiency and user experience.

The technology to understand and manipulate light took centuries to develop, and happened independently across many different cultures. Mirrors have helped to shape the modern human mind while also furthering our understanding of math and science. They are an impressive holdover from the analogue age that doesn’t require electricity yet can produce replicated, moving images at a resolution higher than the human eye can perceive. Cosmoso takes a look at the history of this uniquely high tech piece of our global, human ancestry.

Developing Reflective Tech Before Recorded History

Like a lot of ancient technologies, people were able to develop and perfect image reflection without fully understanding the principles and materials they were manipulating. Creating a mirror in a time before modern science took different paradigms of understanding, such as alchemy, superstition and religious belief.

Human technologies are often inspired by nature. Our ancestors often pondered the meaning of the reflective properties they no doubt noticed in pools of water. When water is flowing, falling or otherwise in turmoil, the light it reflects is scattered but a calm pool of water with a dark surface below it shows a reflection.

Technologies often lead to further inspiration, and the advent of metal smelting and the discovery of glass and crystal lead to a variety of reflective properties humans were able to control. Archeologists have found man made mirrors made of polished obsidian, a natural volcanic glass dated back to 6000 BC in ancient Turkey.

Thousands of years after stone reflective mirrors were created, mirrors made of polished copper were made by ancient Mesopotamians dated to 4000 BC, one thousand years before Egyptians discovered copper smelting and discovered copper reflection on their own, at about 3000 before Christ.

Other types of polished stone mirrors have been found in Central and South America much later around 2000 BC. Ancient Americans developed tech on a later timeline because the land was developed later in the planet’s history by nomadic people who often abandoned technology to live off the land while nomadically exploring previously uninhabited lands.

In times when the only access to your own reflection was an enigmatic piece of polished obsidian, the sense of self was a psychological leap away from modern man’s. Obsidian mirrors were used by various cultures to scry or predict the future, and mirrors of stone were thought to possess magic powers.

Chinese Technology: Far Ahead of the West

Around the time when the Americas were still developing stone technologies, bronze mirrors were being manufactured in 2000 BC China. China was very technologically developed at this time, and able to smelt and create a variety of metals, compounds and amalgams, including a bronze. There are many archeological finds attributed by forensics to Chinese “Qijia” culture. Proprietary secrets forced mirror tech to diverge, and it’s possible to find examples of mirrors made from various metal alloys such as copper and tin, at the same time other parts of Asia were still simply polishing copper smelted from the earth. The tin, copper alloy found in China and India is called speculum metal, which would have been very expensive to produce in it’s time.

Speculum metal coated mirrors brought such a high analogue resolution that people could understand what they looked like, which affected fashion and hairstyles but also began to affect other artforms like dancing and martial arts. Philosophical concepts such as duality, other worlds and multiplicity were suddenly easy to explain via analogy with the help of a mirror.

Speculum metal coated mirrors brought such a high analogue resolution that people could understand what they looked like, which affected fashion and hairstyles but also began to affect other artforms like dancing and martial arts. Philosophical concepts such as duality, other worlds and multiplicity were suddenly easy to explain via analogy with the help of a mirror.

Manipulation of one’s own facial expression, slight of hand and other practiced mannerisms were now able to be studied and documented, creating new layers to the fabric of civilization.

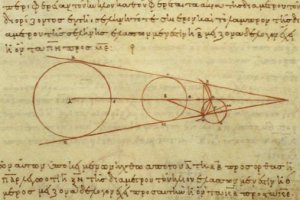

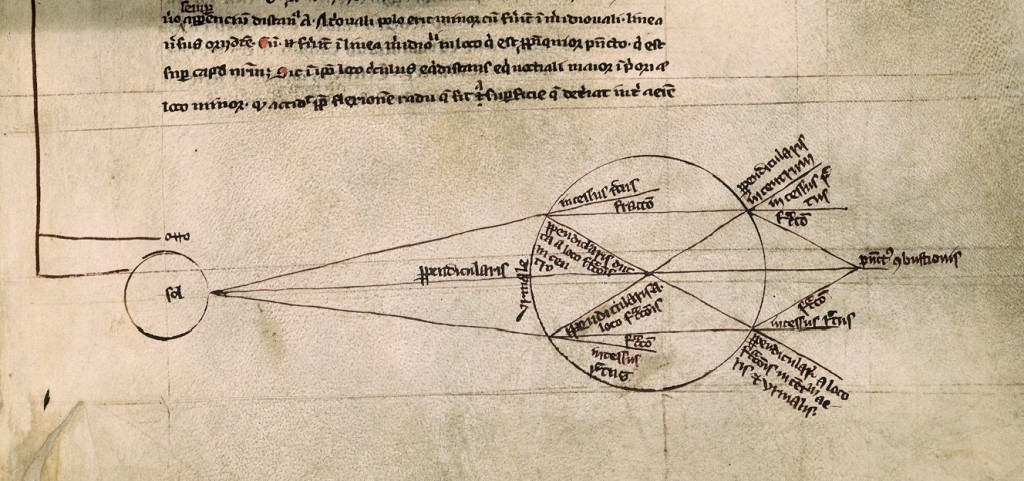

For all of this cultural development, there was no scientific analyzation of why a mirror worked or the light it was reflecting. Before mirror technology could be advanced, there needed to be written, thoughtful investigation of why the tech worked in the first place. This was a slow process in any ancient tech but in a time before light waves and chemistry was understood, it was extremely slow. The earliest written work studying the way light reflects came from Diocles, a Greek mathematician and author of On Burning Mirrors who lived 240 BC – c. 180 BC. Illiteracy and language barriers slowed the technological development of concave and convex curved mirrors another few hundred years.

Mathematics and mirrors will always have a reciprocal relationship, with math and science allowing humanity to dream up new ways of manipulating light and mirrors allowing that manipulation to inspire new questions and explanations. What was once considered magic became the study of the world we inhabit as technology took root in the physical and psychological world humans are trapped in.

Another technological breakthrough happened in ancient Lebanon when metal-backed glass mirrors were finally invented, first century AD. Roman author Pliny wrote his famous work, “Natural History” in 77 AD, where he mentions gold-leafed glass mirrors, though none from that time have survived. Most Roman mirrors were glass coated with lead which might have used the same technological process and just been much cheaper than gold.

Discovering the text On Burning Mirrors, Greco-Egyptian writer, Ptolemy, began to experiment with curved polished iron mirrors. He was able to peak the interest of wealthy benefactors and study with impunity. His writings discuss plane, convex spherical, and concave spherical mirrors. This was circa 90 AD. The image above describes light passing through a cylindrical glass of water.

Silvered Glass & the Modern Age:

Silver-mercury amalgams were found in archeological digs and antique collections dating back to 500 AD China. Renaissance Europeans traded with the known world, perfecting a tin-mercury amalgam and developing the most reflective surfaces known until the 1835 invention of silvered-glass mirrors. Historical records seem to credit German chemist Justus von Liebig with silvered glass but glassworkers guild records obscure the story behind it. Silvered glass coats metallic silver on the back of the reflective glass by utilizing silver nitrate in the dawning of applied chemistry. Silver is expensive but the layer is so thin, and the process so reliable that affordable mirrors began to show up in working class households across the planet ever since.

|

Jonathan Howard

Jonathan is a freelance writer living in Brooklyn, NY |