From folklore to children’s stories, it seems humans have always been fas cinated with spider silk, the diverse material produced in abundance, at will from the body of nearly all species of spider. Studying the biomechanics of the spinnerets and the chemicals that combine to produce various textures of silk at a molecular level has allowed scientists a new perspective on efficiency and biosynthesis.

cinated with spider silk, the diverse material produced in abundance, at will from the body of nearly all species of spider. Studying the biomechanics of the spinnerets and the chemicals that combine to produce various textures of silk at a molecular level has allowed scientists a new perspective on efficiency and biosynthesis.

The golden orb-weaver spider (Nephila clavipes) produces so much silk everyday it has become the most studied spider in the world, and was even included in a trip to the International Space Station in a special terrarium. Golden Orb-Weaver silk is 30 times thinner than your average human hair. If Spider-man were to produce a proportionate thickness of the same material the line would likely hold, maybe even hold the weight of two adult humans(Valigra, 1999.)

It’s hard to find a material as strong while still retaining the flexibility and elasticity of spider silk. Maybe impossible. The dragline of the average spider silk is five times more durable than the Kevlar used in bullet-proof vests(Benyus, 2002, p. 132), plus, it’s lighter and breathes better. Kevlar is a petroleum product and requires pressurized vats of intensely hot sulfuric acid (Benyus, 2002, p.135; 2001). Biologically-inspired materials might be drastically more efficient on energy costs to create. Oil-based synthetic molecules often create dangerous bi-products which are hazardous to handle, expensive to store and virtually impossible to dispose. Spiders create superior materials with a very small amount of energy, heat or byproducts. (Benyus, 2001). NASA studies found that Gold Orb Spider spinneret systems can be so efficient they include reusing spider silk eaten and ingested after use.

It’s hard to find a material as strong while still retaining the flexibility and elasticity of spider silk. Maybe impossible. The dragline of the average spider silk is five times more durable than the Kevlar used in bullet-proof vests(Benyus, 2002, p. 132), plus, it’s lighter and breathes better. Kevlar is a petroleum product and requires pressurized vats of intensely hot sulfuric acid (Benyus, 2002, p.135; 2001). Biologically-inspired materials might be drastically more efficient on energy costs to create. Oil-based synthetic molecules often create dangerous bi-products which are hazardous to handle, expensive to store and virtually impossible to dispose. Spiders create superior materials with a very small amount of energy, heat or byproducts. (Benyus, 2001). NASA studies found that Gold Orb Spider spinneret systems can be so efficient they include reusing spider silk eaten and ingested after use.

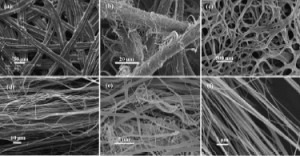

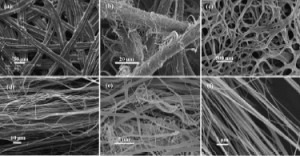

Electron-microscope imaging shows the variety of textures a single spider can produce from its body.

Spider silk would be so incredibly useful it might not even be possible to anticipate the range of products it might inspire. Most materials knows to man are either elastic or have a high tensile strength but some pider silks fall in a rare category of scoring high in both areas (Benyus, 2001). Spider silk can stretch 40 percent longer than its relaxed state without losing any of it’s shape when it returns. Even the stretchiest nylon can’t perform that way (Benyus, 2002, p.132; 2001). Dupont materials compared silk to current steel cables used on bridges and standing structures worldwide and found dragline spider silk strong enough to be used as the quick-stop brake system on a jet in flight on an aircraft carrier (Valigra, 1999), at a fourth of the thickness of steel cables.

“spider silk is so strong and resilient that on the human scale, a web resembling a fishing net could catch a passenger plane in flight. If you test our strongest steel wire against comparable diameter silk they would have a similar breaking point. But if confronted with multiple pressures, such as gale-force winds, the silk can stretch as well; something steel cannot do” (Benyus, 2001, 2002).

Spiders evolved the ability to spin a web strong and versatile enough to allow it to run across, pull and twist into position and manipulate with its many legs in order to trap prey, set complicated tricks into actio n and run along without becoming entangled. The elasticity and strength of the web are partly why it is so easy for another species to become ensnared. Researchers who have taken the time to examine closely have realized in awe the potential for application in spaceflight, industrial, commercial and even fashion industries.

n and run along without becoming entangled. The elasticity and strength of the web are partly why it is so easy for another species to become ensnared. Researchers who have taken the time to examine closely have realized in awe the potential for application in spaceflight, industrial, commercial and even fashion industries.

Spider silk also shows incredible tolerance for colder temperatures without becoming brittle or falling apart. Spiders are able to hide underground or near the warm trunk of a tree and return to their outdoor webs later to repair and rebuild what is largely left intact. These cold-tolerant properties lend superior promise to its potential as aan advanced suitable for bridge cables, as well as lightweight parachute lines for outdoor climbing in military and camping equipment. Scientists have been hyping up its many  potential medical applications such as sutures and replacement ligaments (Benyus, 2001) and as a durable substance to fabricate clothing and shoes (made of “natural fibers”) and synthetic moldable solid material that can create rust-free panels and hyper durable car bumpers. (Lipkin, R., 1996).

potential medical applications such as sutures and replacement ligaments (Benyus, 2001) and as a durable substance to fabricate clothing and shoes (made of “natural fibers”) and synthetic moldable solid material that can create rust-free panels and hyper durable car bumpers. (Lipkin, R., 1996).

“if we want to manufacture something that’s at least as good as spider silk, we have to duplicate the processing regime that spiders use” Christopher Viney, early biomimetic proponent (Benyus, 2002, pp. 135-6).

Take a look at the fascinating process as a spider creates silk and you will find something that more closely resembles human technology than animal biology. Spiders have evolved to create something highly specialized without tools or any sort of special diet requirements to fuel autosynthesis of silk. Spider silk is formed out of liquid proteins within the spider’s abdomen. Several complex chemicals in a cocktail travel through the duct of a narrow gland. The substance is squeezed out in a very controlled manner through any combination of six nozzles called spinnerets. the protein collected from eating insects and various vegetable matters “emerges an insoluble, nearly waterproof, highly ordered fiber” (Benyus 2001).

Most spiders can produce a few different types of of silks. They can make threads that can be used to build structures, a strong dragline, or an elastic cable for repelling and reusing while creating the foundation for a web. They can make a sticky, wet line that clings to itself and most other surfaces for fastening strong structures, making cocoons and trapping prey. There is much to be learned because all of human scientific knowledge on the subject still comes from a handful of studies of only fifteen or more spiders to date. There are 40,000 spider species, most of which we know almost nothing about. There might be even better silk from some species.

“But yes there is probably a tougher, stronger, stiffer fiber being produced right this minute by a spider we know nothing about. A spider whose habitat may be going up in smoke” Viney (Benyus, 2002, pp.138-40).

n and run along without becoming entangled. The elasticity and strength of the web are partly why it is so easy for another species to become ensnared. Researchers who have taken the time to examine closely have realized in awe the potential for application in spaceflight, industrial, commercial and even fashion industries.

n and run along without becoming entangled. The elasticity and strength of the web are partly why it is so easy for another species to become ensnared. Researchers who have taken the time to examine closely have realized in awe the potential for application in spaceflight, industrial, commercial and even fashion industries.