The Middle Ages has long suffered an unfortunate reputation as being a dark period of violence and superstition. It was a time when disease ran rampant – particularly the infamous Black Death, which may have wiped out as much as one-third of Europe in the 14th century as it made its way from China’s Silk Road. Western medicine seemed helpless against the waves of plague – something that would again ravage London in the 17th century, and is now attributed to three strains of plague transmitted by the bacteria Yersinia pestis.

While medieval physicians didn’t know about microbes, however, it doesn’t mean that their medicine was entirely useless. While there may not have been many ancient elixirs effective against plague, one remedy might actually be an effective weapon against a very modern type of plague: antibiotic-resistant superbacteria.

Researchers at the University of Nottingham in Great Britain successfully replicated a medieval potion and subsequently tested it against one strand of bacteria that is notoriously aggressive and prevalent in hospitals: staphylococcus aureus, more commonly known as MRSA. The remedy is over a millennia old and was first developed by populations of Anglo-Saxon that occupied Britain in the early Middle Ages.

If the name sounds familiar – that’s because it is – the town just a breath away from the legendary Sherwood Forest, which now harbors an Institute for Medieval Research. Some historians leafed through a 1,000 year old manuscript known as “Bald’s Leechbook,” where they found a remedy for eye infection – perhaps something that Robin Hood’s band of merrymen would be prone to – scratched corneas after an armed skirmish with Nottingham’s sheriff.

The infection would typically be treated by an herbalist, mixing the concoction in a brass vessel, along with a remedy of bile, mixed in the cow’s stomach, and some freshly picked Allium that grows in the forest, a bulb closely related to garlic.

Viking studies professor Christina Lee first found the potion and went about translating the recipe from Old English. While herbalists had hardly the same training as today’s medical doctors, they had to at least have some method for determining the right treatment for different types of infection. It must have been a bit like working in the dark, too, as they had a few centuries to go before germ theory of disease would be discovered.

To recreate the salve, she turned to chemists working at the university’s Center for Biomolecular Sciences.

It might have seemed like an unusual request, but little did Lee know that it would be a crucial step at addressing a growing concern. Antibiotics are often specific to one strain of pathogens, and dependent on entire generations of bacteria being wiped out. However, bacteria replicate at a rapid pace – producing several generations in just a matter of 24 hours. If one bacterial cell develops a tolerance for antibiotics, it can swiftly pass this along through a primitive evolutionary process known as horizontal gene transfer, eventually producing a generation of superbacteria. In hospitals, where many antibiotics are administered regularly, the environment for superbacteria is more inviting.

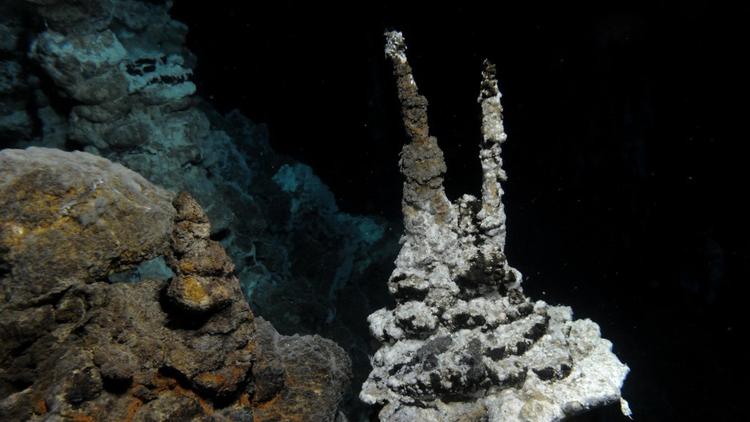

Lee’s investigation might actually have opened the doors to a new way of approaching the problem, going after antimicrobial agents that are found in nature, something that caught the attention of microbiologist Freya Harrison. In her lab, the chemists followed the recipe with precision, yielding four individual batches with fresh ingredients. They even used the medieval methods for cultivating it, with a brass sheet as their brewing container, where they poured the distilled water.

They then used lab conditions to set off the growth of a strain of Staphylococcus aureus bacteria, which had grown resistant to the standard drug Methicillin, each grown in a small piece of collagen. The impact of the salve was astounding: roughly only one in 1,000 bacterial cells survived.

Harrison said that she was “absolutely blown away” by the power of this antique concoction, something she initially suspected would have a slight antibacterial effect. Some ingredients of the salve – namely copper and bile salts showed some lethal effect on the bacteria in the lab. Plants in the garlic family have also been known for producing chemicals that will intercept the ability of healthy bacteria to damage tissue that had been infected – a property that has made garlic cloves a time-honored cold remedy.

There’s something to say about the whole being greater than the sum of its parts, however. When they combined all their ingredients, under medieval conditions, they found some even more exciting discoveries under the microscope. The eye salve acted more aggressively than the control substance they applied to another set of bacteria, with adhesive particles that were able to break through the bacteria’s sticky coating, tearing apart colonies of mature bacteria that showed little reaction to antibiotic treatments.

So potent was the concoction developed by Harrison’s research team that they later diluted the salve, seeing how much dose was needed to be effective. Even in situations where populations of S. aureus survived, communication between bacteria in the colony was disrupted – perhaps the most intriguing aspect of the salve. Without any cross-talk between the cells, the genes that promote antibiotic resistance could not be signaled – an important and organic way to attacking bacterial infections.

This new and unlikely coalition between historians – especially in the very specialized branch of medieval medicine – and microbiologists led to the development of a new program called AncientBiotics at Nottingham, where researchers are seeking funding to further explore this new parallel between the sciences and humanities.

“We know that MRSA-infected wounds are exceptionally difficult to treat in people and in mouse models,” said Kendra Rumbaugh, who performed the testing of Bald’s remedy on MRSA-infected skin wounds in mice. “We have not tested a single antibiotic or experimental therapeutic that is completely effective,” added Rumbaugh, a professor of surgery at Texas Tech University’s School of Medicine. But she said the ancient remedy was at least as effective – “if not better than the conventional antibiotics we used.”

|

James Sullivan

James Sullivan is the assistant editor of Brain World Magazine and a contributor to Truth Is Cool and OMNI Reboot. He can usually be found on TVTropes or RationalWiki when not exploiting life and science stories for another blog article. |