Tiny satellites, some smaller than a shoe box, are currently orbiting around 200 miles above Earth, collecting data about our planet and the universe. It’s not just their small stature but also their accompanying smaller cost that sets them apart from the bigger commercial satellites that beam phone calls and GPS signals around the world, for instance. These SmallSats are poised to change the way we do science from space. Their cheaper price tag means we can launch more of them, allowing for constellations of simultaneous measurements from different viewing locations multiple times a day – a bounty of data which would be cost-prohibitive with traditional, larger platforms.

Called SmallSats, these devices can range from the size of large kitchen refrigerators down to the size of golf balls. Nanosatellites are on that smaller end of the spectrum, weighing between one and 10 kilograms and averaging the size of a loaf of bread.

Starting in 1999, professors from Stanford and California Polytechnic universities established a standard for nanosatellites. They devised a modular system, with nominal units (1U cubes) of 10x10x10 centimeters and 1kg weight. CubeSats grow in size by the agglomeration of these units – 1.5U, 2U, 3U, 6U and so on. Since CubeSats can be built with commercial off-the-shelf parts, their development made space exploration accessible to many people and organizations, especially students, colleges and universities. Increased access also allowed various countries – including Colombia, Poland, Estonia, Hungary, Romania and Pakistan – to launch CubeSats as their first satellites and pioneer their space exploration programs.

Initial CubeSats were designed as educational tools and technological proofs-of-concept, demonstrating their ability to fly and perform needed operations in the harsh space environment. Like all space explorers, they have to contend with vacuum conditions, cosmic radiation, wide temperature swings, high speed, atomic oxygen and more. With almost 500 launches to date, they’ve also raised concerns about the increasing amount of “space junk” orbiting Earth, especially as they come almost within reach for hobbyists. But as the capabilities of these nanosatellites increase and their possible contributions grow, they’ve earned their own place in space.

From proof of concept to science applications

When thinking about artificial satellites, we have to make a distinction between the spacecraft itself (often called the “satellite bus”) and the payload (usually a scientific instrument, cameras or active components with very specific functions). Typically, the size of a spacecraft determines how much it can carry and operate as a science payload. As technology improves, small spacecraft become more and more capable of supporting more and more sophisticated instruments.

These advanced nanosatellite payloads mean SmallSats have grown up and can now help increase our knowledge about Earth and the universe. This revolution is well underway; many governmental organizations, private companies and foundations are investing in the design of CubeSat buses and payloads that aim to answer specific science questions, covering a broad range of sciences including weather and climate on Earth, space weather and cosmic rays, planetary exploration and much more. They can also act as pathfinders for bigger and more expensive satellite missions that will address these questions.

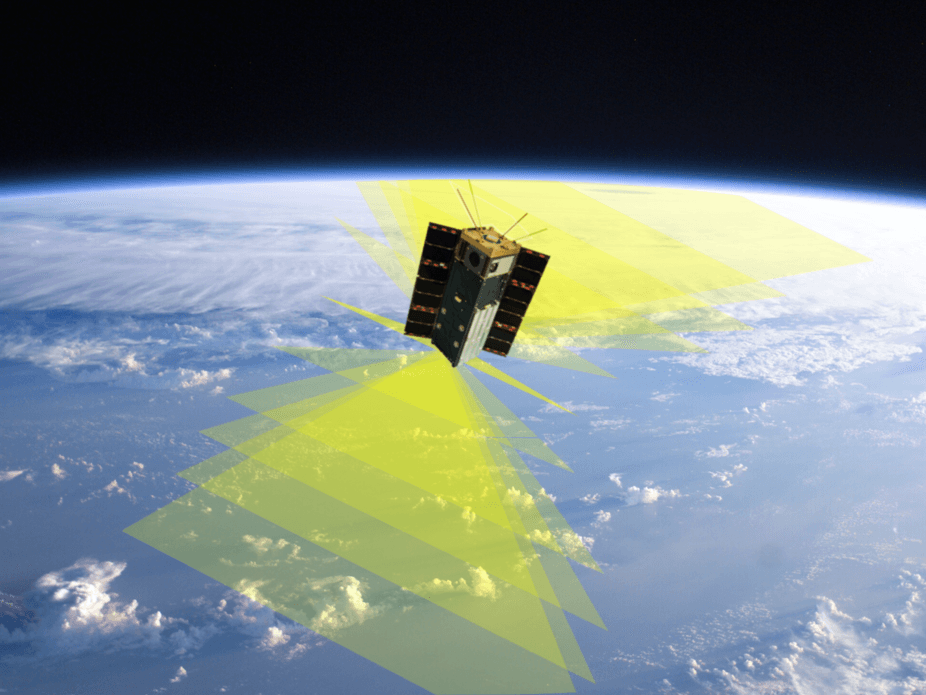

I’m leading a team here at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County that’s collaborating on a science-focused CubeSat spacecraft. Our Hyper Angular Rainbow Polarimeter (HARP) payload is designed to observe interactions between clouds and aerosols – small particles such as pollution, dust, sea salt or pollen, suspended in Earth’s atmosphere. HARP is poised to be the first U.S. imaging polarimeter in space. It’s an example of the kind of advanced scientific instrument it wouldn’t have been possible to cram onto a tiny CubeSat in their early days.

Spacecraft: SDL, Payload:UMBC, CC BY-ND

Funded by NASA’s Earth Science Technology Office, HARP will ride on the CubeSat spacecraft developed by Utah State University’s Space Dynamics Lab. Breaking the tradition of using consumer off-the-shelf parts for CubeSat payloads, the HARP team has taken a different approach. We’ve optimized our instrument with custom-designed and custom-fabricated parts specialized to perform the delicate multi-angle, multi-spectral polarization measurements required by HARP’s science objectives.

HARP is currently scheduled for launch in June 2017 to the International Space Station. Shortly thereafter it will be released and become a fully autonomous, data-collecting satellite.

SmallSats – big science

HARP is designed to see how aerosols interact with the water droplets and ice particles that make up clouds. Aerosols and clouds are deeply connected in Earth’s atmosphere – it’s aerosol particles that seed cloud droplets and allow them to grow into clouds that eventually drop their precipitation.

Martins, UMBC, CC BY-ND

This interdependence implies that modifying the amount and type of particles in the atmosphere, via air pollution, will affect the type, size and lifetime of clouds, as well as when precipitation begins. These processes will affect Earth’s global water cycle, energy balance and climate.

When sunlight interacts with aerosol particles or cloud droplets in the atmosphere, it scatters in different directions depending on the size, shape and composition of what it encountered. HARP will measure the scattered light that can be seen from space. We’ll be able to make inferences about amounts of aerosols and sizes of droplets in the atmosphere, and compare clean clouds to polluted clouds.

In principle, the HARP instrument would have the ability to collect data daily, covering the whole globe; despite its mini size it would be gathering huge amounts of data for Earth observation. This type of capability is unprecedented in a tiny satellite and points to the future of cheaper, faster-to-deploy pathfinder precursors to bigger and more complex missions.

HARP is one of several programs currently underway that harness the advantages of CubeSats for science data collection. NASA, universities and other institutions are exploring new earth sciences technology, Earth’s radiative cycle, Earth’s microwave emission, ice clouds and many other science and engineering challenges. Most recently MIT has been funded to launch a constellation of 12 CubeSats called TROPICS to study precipitation and storm intensity in Earth’s atmosphere.

For now, size still matters

But the nature of CubeSats still restricts the science they can do. Limitations in power, storage and, most importantly, ability to transmit the information back to Earth impede our ability to continuously run our HARP instrument within a CubeSat platform.

So as another part of our effort, we’ll be observing how HARP does as it makes its scientific observations. Here at UMBC we’ve created the Center for Earth and Space Studies to study how well small satellites do at answering science questions regarding Earth systems and space. This is where HARP’s raw data will be converted and interpreted. Beyond answering questions about cloud/aerosol interactions, the next goal is to determine how to best use SmallSats and other technologies for Earth and space science applications. Seeing what works and what doesn’t will help inform larger space missions and future operations.

The SmallSat revolution, boosted by popular access to space via CubeSats, is now rushing toward the next revolution. The next generation of nanosatellite payloads will advance the frontiers of science. They may never supersede the need for bigger and more powerful satellites, but NanoSats will continue to expand their own role in the ongoing race to explore Earth and the universe.

![]()

J. Vanderlei Martins, Professor of Physics, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.