Category Archives: Women’s Issues

Is there really a single ideal body shape for women?

Many scholars of Renaissance art tell us that Botticelli’s Birth of Venus captures the tension between the celestial perfection of divine beauty and its flawed earthly manifestation. As classical ideas blossomed anew in 15th-century Florence, Botticelli could not have missed the popular Neoplatonic notion that contemplating earthly beauty teaches us about the divine.

Evolutionary biologists aren’t all that Neoplatonic. Like most scientists, we’ve long stopped contemplating the celestial, having – to appropriate Laplace’s immortal words to Napoleon – “no need of that hypothesis”. It is the messy imperfection of the real world that interests us on its own terms.

My own speciality concerns the messy conflicts that inhere to love, sex and beauty. Attempts to cultivate a simple understanding of beauty – one that can fill a 200-word magazine ad promoting age-reversing snake oil, for example – tend to consistently come up short.

Waist to hip

Nowhere does the barren distinction between biology and culture grow more physically obvious than in the discussion of women’s body shapes and attractiveness. The biological study of body shape has, for two decades, been preoccupied with the ratio of waist to hip circumference.

With clever experimental manipulations of line drawings, Devendra Singh famously demonstrated that images of women with waists 70% as big as their hips tend to be most attractive. This 0.7:1 waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), it turns out, also reflects a distribution of abdominal fat associated with good health and fertility.

Singh also showed that Miss America pageant winners and Playboy playmates tended to have a WHR of 0.7 despite changes in the general slenderness of these two samples of women thought to embody American beauty ideals.

Singh’s experiments were repeated in a variety of countries and societies that differ in both average body shape and apparent ideals. The results weren’t unanimous, but a waist-to-hip ratio of 0.7 came up as most attractive more often than not. The idea of an optimal ratio is so appealing in its simplicity that it became a staple factoid for magazines such as Cosmo.

There’s plenty to argue about with waist-hip ratio research. Some researchers have found that other indices, like Body Mass Index (BMI) explain body attractiveness more effectively.

But others reject the reductionism of measures like WHR and BMI altogether. This rejection reaches its extremes in the notion that ideas of body attractiveness are entirely culturally constructed and arbitrary. Or, more sinisterly, designed by our capitalist overlords in the diet industry to be inherently unattainable.

The evidence? The observation that women’s bodies differ, on average, between places or times. That’s the idea animating the following video, long on production values, short on scholarship and truly astronomic on the number of hits (21 million-plus at the time of writing):

I note that Botticelli’s Venus looks more at home in the 20th Century than among the more full-figured Renaissance “ideals”. So do the Goddesses and Graces in La Primavera. Perhaps there was room for more than one kind of attractive body in the Florentine Renaissance? Or is the relationship between attractiveness and body shape less changeable and more variegated than videos like the one above would have us believe?

Not that I’m down on body shape diversity. Despite the fact that there seems to be only one way to make a supermodel, real women differ dramatically and quite different body types can be equally attractive. The science of attractiveness must grapple with variation, both within societies and among cultures.

Enter the BodyLab

For some years our research group has wrestled with exactly these issues, and with the fact that bodies vary in so many more dimensions than just their waists and their hips. To that end, we established the BodyLab project, a “digital ecosystem” in which people from all over the internet rate the attractiveness of curious-looking bodies like the male example below.

Rob Brooks/BodyLab.biz

We call it a “digital ecosystem” not to maximise pretentiousness, but because this experiment involved multiple generations of selection and evolution. We started with measurements of 20 American women, a sample representing a wide variety of body shapes.

We then “mutated” those measures, adding or subtracting small amounts of random variation to each of 24 traits. Taking these newly mutated measures we built digital bodies, giving them an attractive middle-grey skin tone in an attempt to keep variation in skin colour, texture etc out of the already complex story.

If you want to help out with our second study, on male bodies, visit BodyLab and click through to Body Shape Study and then Rate Males (Generation 6).

This all involved considerable technologic innovation, resulting in an experiment unlike any other. We had a population of bodies (120 per generation) that we could select after a few thousand people had rated them for attractiveness. We then “bred” from the most attractive half of all models and released the new generation into the digital ecosystem.

What did we find? In a paper just published at Evolution & Human Behavior, the most dramatic result was that the average model became more slender with each generation. Almost every measure of girth decreased dramatically, whereas legs and arms evolved to be longer.

Rob Brooks

That may not seem surprising, particularly because the families “bred” from the most overweight individuals at the start of the experiment were eliminated in the first few generations.

But, after that, more families remained in the digital ecosystem, surviving generation after generation of selection, than we would have expected if there was a single most attractive body type. The Darwinian process we imposed on our bodies had started acting on the mutations we added during the breeding process.

More meaningful than the mean

Those “mutations” that we introduced allowed bodies to evolve free from all the developmental constraints that apply to real-world bodies. For example, leg lengths could evolve independently of arm lengths. Waists could get smaller even as thighs got bigger.

When we examined those five families that lasted longest as our digital ecosystem evolved, we observed a couple of interesting nuances.

First, selection targeted waist size itself, rather than waist-hip ratio. No statistical model involving hip size (either on its own or in waist-hip ratio) could come close to explaining attractiveness as well as waist size alone. Our subjects liked the look of slender models with especially slender waists. There was nothing magical about a 0.7 waist-to-hip ratio.

Second, within attractive families, which were the more slender families to begin with, evolution bucked the population-wide trend. These bodies began evolving to be more shapely, with bigger busts and more substantial curves.

It turns out there’s more than one way to make an attractive body, and those different body types evolve to be well-integrated. That’s a liberating message for most of us: evolutionary biology has more to offer our understanding of diversity than the idea that only one “most attractive” body (or face, or personality) always wins out.

What about the cultural constructionists? Are body ideals arbitrary, or tools of the patriarchal-commercial complex?

Our results suggest that the similarities between places, and even between male and female raters, are pretty strong: the 60,000 or so people who viewed and rated our images held broadly similar ideas of what was hot and what was not. But their tastes weren’t uniform. We think most individuals could see beauty in variety, if not in the full scope of diversity on offer.

What’s cool about our evolving bodies, however, is that we can run the experiment again and again. We can do so with different groups of subjects, or even using the same subjects before and after they’ve experienced some kind of intervention (perhaps body-image consciousness-raising?). I’m hoping we can use them to look, in unprecedented depth, at the intricate ways in which experience, culture and biology interact.

![]()

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Read the original article.

Leaks, Revenge Porn, Consent and the Future of Privacy in the Information Age

The tide is turning on revenge pornographers, “purveyors of sexually explicit media that is publicly shared online without the consent of the pictured individual”. In almost any public context on the internet, most Americans are almost unanimous in condemning the nature of the privacy violations behind revenge porn. Liberals who want the concept of consent front and center in any contemporary debate about sex have also lead the conversation about privacy debates and can easily get on board with the support for the overwhelmingly female victims of revenge porn. Conservatives could seize not only a new opportunity to regulate porn in a way that reaches across the aisle but chance to condemn an aspect of pornography. “Revenge porn mogul” might be the least likeable role the internet age has to offer and now it is poised to become one that marks the transition to the second generation raised on the internet. It’s a crime for the ages. Like a lot of what happens online, it’s being punished, legislated, debated, rising and hopefully falling – all within a generation.

Hunter Moore recently plead guilty to hacking charges and ultimately will be punished for a felony conspiracy to hack email accounts to access nude or pornographic pictures. Is there anyone supporting these revenge porn sites without acknowledging it as a vice? Any open supporters? How did revenge porn, something so universally frowned on, become a profitable business for multiple sites and their administrators? First of all, there is an audience for it. Pornography in general is a successful and diverse media industry but that industry is home to several active arguments. These arguments have fluctuating dynamics as the cultural contexts and tastes morph over time. When nudes are leaked or revenge porn is uploaded crucial aspects of other porn-related debates are accented. Aspects like: how consent is portrayed, how publishing rights are managed and protected, and how regular pornography use affects the human psyche. The number of porn watchers is so high the revenge sites were able to stay in business despite public outcry and condemnation.

Is revenge pornography going to persist despite the first steps toward a coming prohibition? Is there a coming prohibition? Will prohibition work?

What is the nature of the post-modern privacy debate? How much privacy can we guarantee ourselves under the current system, and how can we protect it? How is our right to privacy defined the evolving light of interactive media, smart devices, ubiquitous cameras and social media? How can one most effectively respond to privacy violations in the contemporary context?

A changing political landscape ahead for the privacy debate. Will the call for information transparency eventually prove to be a strong counter argument against individual privacy? If corporations, government workers, military entities and criminals outside the reach of current law enforcement are to be held accountable their privacy must be violated. The vocabulary changes and people begin to talk about security and the individual is actually tasked with protecting not only his or her own personal secrets but to sacrifice informational privacy for the sake of the group or entity’s security. People can feel threatened and become intimidated into complacency or even become complicit in information-related crimes. The material is vast and the precedent has yet to be set leaving employees subject to situations where the law has yet to be written, and a social doctrine isn’t yet forged.

Read more about the current state of the internet at:

World Cyberwar: Six Internet News Stories in 2015 Blur the Line Between Sci Fi and Reality

|

Jonathan Howard

Jonathan is a freelance writer living in Brooklyn, NY |

Five research-backed reasons we wear makeup

Prozac and PMS – how antidepressants could help with that painful time of the month

By Jonathan Fry, UCL

Already widely prescribed as antidepressants, SSRIs such as fluoxetine (the non-brand name for Prozac) have gained increasing acceptance over the past 20 years in the treatment of premenstrual syndrome (PMS).

Recent research has given us an idea of the way these drugs do this, which should pave the way to improved treatment.

SSRIs, short for selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors, are thought to work by increasing levels of serotonin, a neurotransmitter that relays information between nerve cells in the brain. Once a message has been sent, serotonin is reabsorbed but SSRIs stop this from happening, leaving more of the chemical in the brain. As serotonin is linked to good mood it is extensively used to treat depressive and anxiety disorders.

In treating PMS, however, these drugs appear to do something else instead, inhibiting an enzyme involved in the metabolism of the ovarian steroid hormone progesterone.

Premenstrual disorders

Most women have experienced some of the symptoms of PMS, which include irritability, anxiety, fatigue, sleep disturbance and an increased sensitivity to pain, as a normal part of their menstrual cycle. While about a quarter seek treatment for the more loosely defined premenstrual syndrome, an estimated 5% of women experience a severe and debilitating form called premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) during their reproductive years.

We know that PMS is caused by changes in ovarian hormone production during the menstrual cycle, in particular the approximately ten-fold rise in progesterone after ovulation, followed by a sharp fall in its secretion in the week before menstruation. Importantly, this rapid fall in ovarian progesterone secretion is accompanied by a decline in its metabolite allopregnanolone, a steroid which acts as a potent sedative and tranquilising agent.

In other words, premenstrual women are undergoing withdrawal from the internal tranquiliser allopregnanolone. This is a major contributory factor in PMS.

So how to treat it?

If PMS is caused by cyclic ovarian activity, then one potential cure is to stop ovulation. Of course, this is what happens in pregnancy and one interesting idea is that PMS evolved to drive women away from an infertile pair bond.

There are drugs which will also prevent ovulation but, if used over the long-term, they require additional therapy with synthetic hormones to replace the missing ovarian oestrogens and progesterone. Then there are contraceptive steroids that can suppress ovulation and cause some relief from PMS, but symptoms can recur during the withdrawal bleed period.

Replacement therapy with progesterone is also problematic as this can worsen the symptoms and make some patients drowsy, probably because of the metabolism of progesterone into excessive amounts of the sedative allopregnanolone.

The use of fluoxetine

An ideal treatment for PMS would be a drug which slows the fall in allopregnanolone towards the end of the menstrual cycle. This appears to be how fluoxetine works. Treatment with fluoxetine and other SSRIs can increase the concentration of allopregnanolone in rat and mouse brains, a response which can be seen within an hour and at doses lower than those required to inhibit the re-uptake of serotonin. Low doses of SSRIs can also increase allopregnanolone in human brains.

A recent study in female rats showed that low doses of fluoxetine which didn’t block the re-uptake of serotonin but did increase allopregnanolone in the brain, also prevented the development of PMS-like symptoms. Interestingly, they also blocked the increase in excitability of brain circuits mediating responses to fear.

Fluoxetine acts on a biochemical switch

The ovary and brain convert progesterone to allopregnanolone in two steps, both controlled by enzymes. In the first step, progesterone is converted into a steroid called 5α-dihydroprogesterone – an inactive precursor. The second step is regulated by a pair of enzymes, one of which transforms this precursor into allopregnanolone, while the other converts allopregnanolone back into the inactive precursor. So the level of allopregnanolone is controlled by the balance of these opposing activities – essentially, a biochemical switch.

In rat brains, fluoxetine blocks the enzyme that converts allopregnanolone back into the inactive precursor. It also has the same effect on the human enzyme. So, fluoxetine should blunt the premenstrual fall in allopregnanolone.

PMS by Shutterstock

Sex and age differences

If fluoxetine elevates allopregnanolone in the brain in this way then we can understand why younger women of reproductive age, with regular fluctuations of allopregnanolone, are more sensitive to SSRIs than men, who produce continuous low levels of this steroid.

This sex difference can be observed in rats. Indeed, there is growing evidence from animal studies that elevation of brain allopregnanolone may be an important part of the antidepressant response to SSRIs.

The elevation of allopregnanolone in the brain from only low doses of fluoxetine also explains why women with PMS respond so quickly – within two days – to this drug. By contrast, full antidepressant responses to larger doses of fluoxetine which alter brain serotonin function can take up to two months.

There is therefore a basis here for the treatment of PMS with low doses of SSRIs, given intermittently to reduce the side effects of these drugs, which include nausea, diarrhoea, anorexia, insomnia, tiredness and sexual dysfunction. The discovery of an allopregnanolone metabolising enzyme as a target means that we can also hope for the development of more specific drugs for the treatment of PMS.

![]()

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Read the original article.

The contraceptive pill was a revolution for women and men

By Sonia Oreffice, University of Surrey

Carl Djerassi, who died recently aged 91, has been honoured globally for his work.

In his remarkable career he also did pioneering work with antihistamines and topical corticosteroids for inflammation, but it is for his work on the pill that he is rightly world famous: he and his team were the first to synthesise a hormone instrumental to the creation of the oral contraceptive pill as we know it.

Women in control

Birth control innovations have had a remarkable impact on modern societies in the past five decades. They enhanced women’s opportunities to control childbearing and their careers, allowed them to choose contraception and plan fertility independently of their partner or spouse, increased female human capital accumulation, labour market options and earnings.

The dramatic increase in women’s education, college and professional degrees, and participation in the labour market since the 1960s can also be partly explained by birth control innovations.

Human capital

Reliable contraception allows women to invest in their human capital with much less risk and so achieve higher education and professional degrees. By separating sex from procreation and giving women more control over their bodies, it also lifted the “obligation” to marry early.

Tim Ireland/PA Wire

The widespread availability of a very low-cost, highly reliable, easy-to-use technology such as the pill directly improved the well-being of single women, for whom an unwanted pregnancy can be very costly. At the same time, the high rate of usage of this contraceptive and the new fertility and career opportunities it entailed increased the well-being of women in marriages or relationships too.

Birth control technology affected both men’s and women’s ability to make decisions about the number of children they had and when they had them. But such a shift in partners’ fertility decision rights affected the balance of power between men and women, and female empowerment more generally.

A crucial force at play here is the legal and biological asymmetry that has characterised men and women: women do not need to be partnered to become mothers, whereas men cannot enjoy paternity without being in a couple (the legal availability of surrogate mothers partially changes this statement).

Continuing revolution

The birth control revolution is clearly not over yet: recent developments have focused on assisted reproductive technologies, which include IVF and sperm/egg banks. These also enhance freedom of fertility choices, while standing at the other end of the spectrum of birth control methods like the pill.

In principle, a technology that helps women and couples to conceive and have children should have a similar positive impact on female empowerment as the pill because it also allows women to control the timing of childbearing, have children later in life, and to improve choice and opportunities outside marriage.

The pill may help men too

The cultural revolution created by birth control technology innovations such as the pill also contributed to the awareness and, little by little, the social acceptance of working mums, older mums, and children born to cohabiting parents.

The ability to bear children – and its biological and socio-economic implications – still challenges working women, while affecting society well beyond women’s working lives. The pill, along with the other broadly defined birth control technologies, brought more freedom of choice and less constrained planning and timing to couples and singles.

Countries where gender roles are very unequal experience high maternal mortality, restricted or no access to birth control, low female schooling rates and high fertility rates.

Djerassi, and the other scientists who discovered and fine-tuned the birth control pill (at the start it had very high hormonal doses), improved the well-being of millions of women, but also of men, who could live with mothers, wives, female friends and colleagues more satisfied with themselves, with more realised potential and more freedom to choose. I hope men realise this. With knowledge and science, against superstition and prejudice, well-being and equality are pursued.

![]()

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Read the original article.

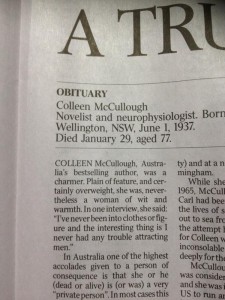

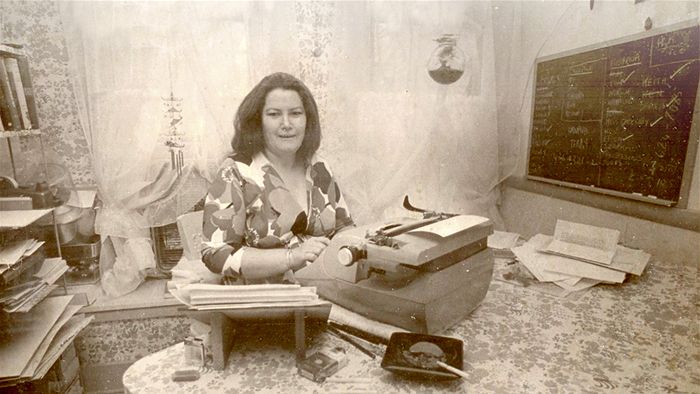

Australian Newspaper Insults Neuroscientist Colleen McCullough

Australia’s national print newspaper, The Australian, printed what can be assumed was an inadvertently insulting obituary of Colleen McCullough, author of the 30-million-copies-sold classic, “The Thorn Birds”. McCullough’s accomplishments took a backseat to this opening line:

“Colleen McCullough, Australia’s best-selling author, was a charmer,” the obituary began. “Plain of feature, and certainly overweight, she was, nevertheless, a woman of wit and warmth. In one interview, she said: “I’ve never been into clothes or figure and the interesting thing is I never had any trouble attracting men.”

McCullough was not just a best-selling novelist. She actually spearheaded the establishment of the neurophysiology department at Sydney’s Royal North Shore Hospital. She spent a decade in the 60’s and 70’s teaching in the Department of Neurology at the Yale Medical School in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. She wrote one of the most watched tv mini-series of all time. That’s right, her physical appearance took a backseat to her position as neuroscientist. So, like, she was fat? Oh, and she wrote 25 novels. NBD

Twitter users responded by posting their own insulting obituaries in solidarity and outrage at #myozobituary (currently trending)trending on Twitter.

Not to be outdone and possibly seeing a chance to take a shot at another print publication, The Washington Post wrote. “Now that I know, here are some obituaries for men, updated lest we fall behind the new standard. Teddy Roosevelt: Resembling a fat walrus in little spectacles, he was, nevertheless, president at one point or another.”

McCullough fought a long string of illnesses before dying last Thursday in a hospital in Norfolk Island, Australia. She had continued writing books for the last 4 decades, with her final novel “Bittersweet” released 2 years ago.

Her most famous novel, “The Thorn Birds,” first printed back in 1977, was made into a television miniseries in 1983 and starred Richard Chamberlain, Rachel Ward and Christopher Plummer. It won four Golden Globe awards. The Australian‘s editor Clive Mathieson declined comment when contacted by The Associated Press over the weekend.

|

Jonathan Howard

Jonathan is a freelance writer living in Brooklyn, NY |

Will abortion opponents use a familiar playbook to push for a 20 week ban?

By Carole Joffe, University of California, San Francisco

On the first day of the new Congress in January, anti-abortion legislators in the House introduced the Pain Capable Unborn Child Protection Act. The bill would have banned abortions after 20 weeks, except for those due to rape, incest or threats to the life of the pregnant woman.

The House had planned to vote on this measure on January 22, the anniversary of the Roe v Wade decision, but at the last minute canceled the vote. GOP lawmakers, many of them women, objected to the stringent rape reporting requirement included in the act.

Reports suggest, however, that this is not the end of the story for the federal 20 week ban and that a modified version of this bill will be voted on at a later date.

Why now?

The 20 week ban is being promoted by abortion opponents because they know it will not only please the extremely important social conservative base of the Republican Party, but will also receive public support.

Although polls show that a majority of Americans want to keep abortion legal, they also show that 64% of Americans would favor making abortion illegal in the second trimester, indicating it is an emotionally charged issue for many.

But one might also question whether a federal 20 week ban is really needed.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, abortions performed at 21 weeks or after account for only 1.4% of all such procedures.

Consider also that abortion has been massively regulated by state legislatures in recent years, with 231 laws passed between 2011 and 2014. These 20 week bans have already passed in 14 states, though lower courts have blocked them in the three places where they’ve been challenged.

Why women seek abortions after 20 weeks

Some women seeking abortions after 20 weeks are doing so for medical reasons. They may have just learned of lethal or serious fetal anomalies. Or they may become very ill themselves, with the pregnancies posing a further risk to their health.

Money is also a factor. Desperately poor women who have trouble finding the funds for an earlier abortion are pushed into a later one as time passes while they gather payment.

In other cases, wanted pregnancies can turn into unwanted ones for personal reasons: the death of a partner, for example, or the serious illness of a child that makes it difficult to contemplate also caring for a newborn.

Junk science and questionable ‘experts’

The rationale for such bans is that the fetus can feel pain at 20 weeks. This claim has been roundly disputed by medical experts, and by organizations such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecology (ACOG). The consensus among these experts is that fetal pain is unlikely before the third trimester (27 weeks).

In pushing for a 20 week ban, anti-abortion politicians are following a tried and true playbook: choose an aspect of abortion provision that is unsettling to a public that is not informed about the science, ignore the testimony of leading medical experts on the abortion issue, and instead, rely on arguments made by alternative “experts,” who may lack the credentials or research background in their purported areas of expertise or draw on so-called junk science.

These kinds of questionable witnesses have been involved in state hearings on legislation banning abortion at 20 weeks.

In 2014 judges criticized the states of Alabama and Texas for using these kinds of witnesses to testify in favor of restrictive abortion policies.

Kevin Lamarque/Reuters

A new ban with an old playbook

This model worked very effectively in the so-called “partial birth abortion” debate a decade ago. In that case, state legislatures and, eventually, Congress passed measures banning the use of a relatively rarely used method of abortion, known in the medical world as Intact Dilation and Evacuation (D&E).

Abortion opponents sensationalized the procedure (“partial birth abortion” is a term that appears nowhere in medical literature) and drew on witnesses – who had never performed an abortion using that method, or, in some cases, any abortions at all – who claimed the method was never necessary.

Medical experts from the abortion-providing community testified that in certain situations, this method was the safest, and medical organizations submitted briefs opposing the ban. Bill Clinton vetoed this bill, but it was signed into law by George W Bush in 2003.

The ban did not include exceptions for the health of the woman – cases where the procedure may be medically necessary and safer for the woman than an alternative. The ban was challenged, and lower court decisions found that it was unconstitutional because it lacked such an exception.

Jonathan Ernst/Reuters

Medical exceptions, shoddy science and the Supreme Court

In 2007 the Supreme Court, in Gonzales v Carhart, heard a challenge to ban.

The court acknowledged that Congress’s findings on the the procedure were wrong, including the assertion that the medical consensus is that the procedure is is never medically necessary. Despite this and the fact that the act contains no health exemption, the court still upheld the law in a 5-4 decision.

It was an unprecedented interference with medical practice on the part of the Court. This decision was particularly disheartening to the abortion rights community.

Justice Anthony Kennedy also seemed to offer legitimacy to a prime example of junk science in the abortion debate: abortion regret syndrome. Writing for the majority, Justice Kennedy, acknowledged that “we find no reliable data to measure the phenomenon,“ while arguing “it seems unexceptionable to conclude some women come to regret their choice to abort the infant life they once created and sustained.”

The American Psychological Association has repeatedly debunked claims that elective abortion “in and of itself causes mental health problems in adult women.” Another major study found that the studies supporting the existence “abortion trauma sydnrome” were riddled with methodological flaws. This study, and others, have found that the best predictor of a woman’s mental health after an abortion is her mental health before the procedure.

What comes next?

The unusual abrupt cancellation of the vote on the 20 week ban bill (which was hastily replaced by another vote on abortion funding) revealed interesting splits within the House Republican caucus, and particularly the concerns of Republican women in swing districts that the exceptions permitted appeared too narrow.

Republican leaders announced that the 20 week ban measure would be voted on at a later, unspecified time. Very likely, the newer version will contain looser requirements for exceptions based on both rape and incest.

Given the present composition of the Senate and a Democratic president in the White House, the federal 20 week ban will not become law if it is re-introduced before the 2016 elections.

But such a ban could very well succeed in the future, depending on the outcome of elections and, particularly, appointments to the Supreme Court. The passage of the numerous abortion restrictions since Roe reveal not only a disregard of the women affected, but also of the health professionals who seek to care for them.

![]()

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Read the original article.